A lab on wheels helps reveal how cannabis affects everything from running to sleep

The inside of the Cannavan provides a space for researchers to conduct experiments that can determine the effects of cannabis that participants have previously consumed in their homes. (Photo by Claudia López Lloreda)

You might never think an inconspicuous white van would be a hub for cannabis research. But by transforming a Dodge Sprinter van into a mobile laboratory, researchers at the University of Colorado Boulder have found that cannabis helps dampen pain in patients with cancer. And they’ve gathered preliminary data showing that cannabis consumption may help athletes enjoy running.

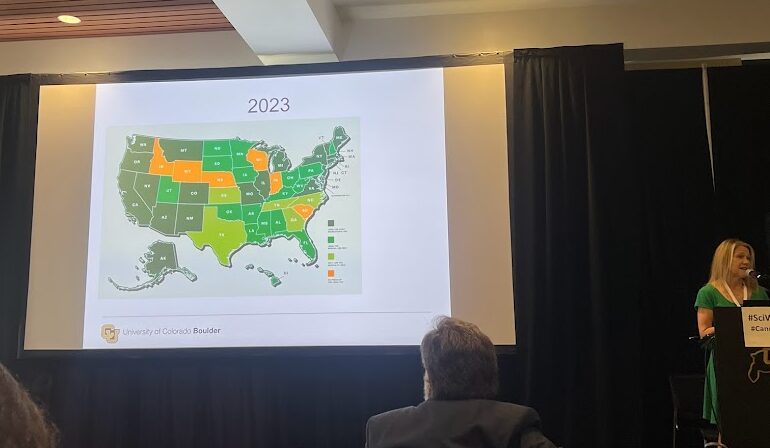

In Colorado, cannabis for recreational use was legalized in 2014, which prompted neuroscientist Angela Bryan to try to understand both the benefits and harms that came with cannabis use. But although cannabis has been legalized for recreational use in 22 additional states and for medicinal use in 38 states, it is still categorized as a Schedule I drug at the federal level. Federal restrictions mean the only source of cannabis products for research by public universities is a farm in Mississippi that grows cannabis for the federal government. The government-grown product is much less potent than cannabis used by the public, constraining research on the use and effects of cannabis.

“Edibles, tinctures, topicals, flowers, concentrates— there’s a lot of variability in the legal market that just doesn’t exist in the products that we can get from the federal government,” Bryan, who is co-director of the CUChange Mobile Pharmacology Laboratory at CU Boulder, said in a presentation at the ScienceWriters2023 conference Oct. 9 as part of the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing’s New Horizons in Science briefings.

To get around this, researchers repurposed the Dodge Sprinter to create the Cannavan. Bryan and her team have research participants buy their own cannabis at legal dispensaries and consume it in their homes. The participants then step into the lab for testing.

“If we can’t bring the people to the lab, our only solution was to bring the lab to the people,” Bryan said.

The team has an array of ongoing studies, with subjects ranging from the general, healthy population to runners to cancer patients.

In a JAMA Psychiatry study, the group tested whether consuming the cannabis flower or a more concentrated form of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), the main psychoactive ingredient in cannabis, led to higher levels of the compound in the blood and consequent behavioral impairment. Despite the difference in potency between the two forms, the groups of participants felt similarly intoxicated and performed similarly in a memory test in which they have to recall a list of shopping items.

Bryan is also looking into the possibility of using cannabis as a way to help patients with cancer, who experience reduced cognitive function and other negative effects from both the cancer and the side effects of treatments such as chemotherapy. A study from Bryan and her team published in April showed that cannabis use for two weeks, no matter what form the patients decided to ingest, helped patients sleep better, decreased pain intensity, and improved subjective cognitive function. “It suggests that we might be able to give cancer patients relief and maybe tamp down some of the negative effects” by using cannabis, Bryan pointed out.

Finally, in findings not yet published and currently being reviewed, researchers had experienced runners hop on a treadmill after having ingested THC, CBD (cannabidiol, an active ingredient that does not cause a “high”) or nothing. With a strap around their waist, participants ran at a set intensity and incline. Runners appeared to have a better time with THC and CBD in their system than without it. In fact, runners who consumed CBD seemed to report more positive emotions and enjoyment than those who consumed THC. Although for the public cannabis may be associated with excessive eating and inactivity, this suggests that cannabis use with exercise thus could help counteract the obesity epidemic by helping people enjoy exercises like running more, Bryan suggested.

Future studies using the mobile van seek to understand how cannabis influences neurological activity, metabolic processes in people with diabetes, and balance in aging populations that might benefit from its use. These studies would help paint a better picture of which compounds within cannabis — whether THC or CBD — might be harmful or helpful for people and how.