Flu and COVID-19 will both surge this winter, but maybe not at the same time

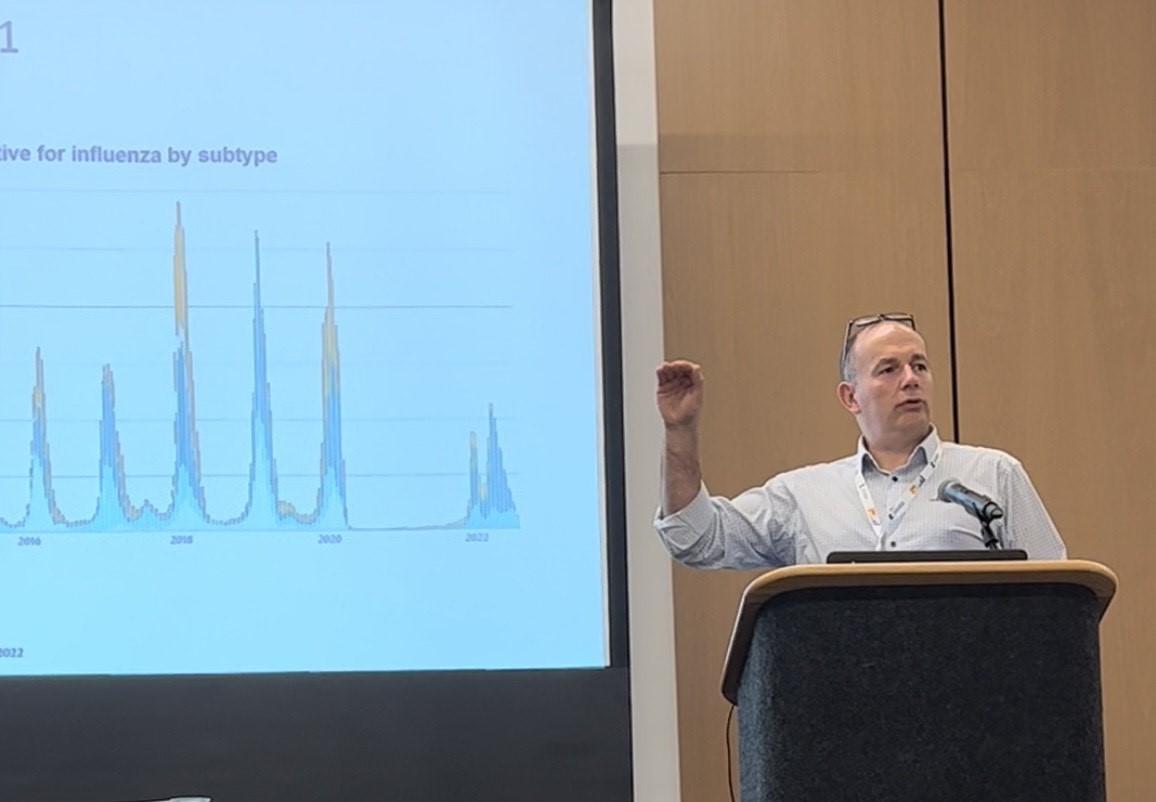

Virologist Richard Webby of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital says COVID-19 and flu might interact with each other in unpredictable ways this winter. (Photo by Megan Keller)

Flu is expected to make a comeback this winter after two years of being suppressed by COVID-19 control measures. But it’s unclear how the two respiratory diseases might interact with each other.

Many experts predict that there could be a combined surge of COVID-19 and flu. But it’s also possible that the viruses could compete, resulting in two distinct waves of infections, each peaking at different times.

“It’s all about how these viruses are directing each other,” Richard Webby, a virologist at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, said Oct. 22 during the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing’s New Horizons in Science briefings at the ScienceWriters2022 conference in Memphis, Tenn.

Before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the timing of the flu season was relatively predictable. In the Northern Hemisphere, cases generally spike between December and March. In the Southern Hemisphere, flu season usually begins in late March and ends in October.

But COVID-19-related masking and physical distancing drove flu cases to their lowest levels in decades. Infectious disease experts warned in 2020 and 2021 that flu viruses and SARS-CoV-2—the virus that causes COVID-19—might circulate together, leading to a “twindemic.” But flu cases remained low, even as hospitals continued to be overwhelmed with patients who had COVID-19.

This year, flu season could look different. Flu began spreading weeks earlier than usual in Australia, which has also recorded more cases this year than four years ago, according to data from the World Health Organization. Because what happens in the south can provide a hint for how intense the season might be in the north, experts predict that the Northern Hemisphere’s flu season will hit early and hard.

Winter is a prime time for flu because the influenza viruses spread best in cold, dry air. But another key factor is how recently people have been exposed. Recovering from an infection or getting a vaccination can teach the immune system to recognize and fight off a virus. Because the flu has lain low during the COVID-19 pandemic, fewer people have post-infection protection, Webby said. That means the 2022-23 flu season could be harsh.

Cases are already on the rise in the southeastern U.S. as well as in some Northeastern and Southwestern states, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. With the novel coronavirus still circulating and making some people severely ill, it’s possible that a bad flu season could add to that burden. But it’s also possible that one virus could interfere with the spread of the other.

“When a human cell gets infected with a virus, that cell starts pumping out chemicals that signal to the immune system for help and to warn other cells around them that a viral infection is happening,” Webby said. That response isn’t specific to any one virus, so people recently infected with the virus that causes COVID-19 might briefly have protection against the flu, and vice versa.

Viruses can compete with one another as they spread among groups of people, some studies suggest. Influenza spikes in the U.K., for example, have been linked to lower levels of infection from viruses that cause colds, according to a 2019 study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

What’s to come with flu and COVID-19 remains up in the air, Webby said. While there are already signs of a flu comeback, predictions for what winter might look like across the U.S. are just guesses.