Homelessness and aging: where 50 is the new 75

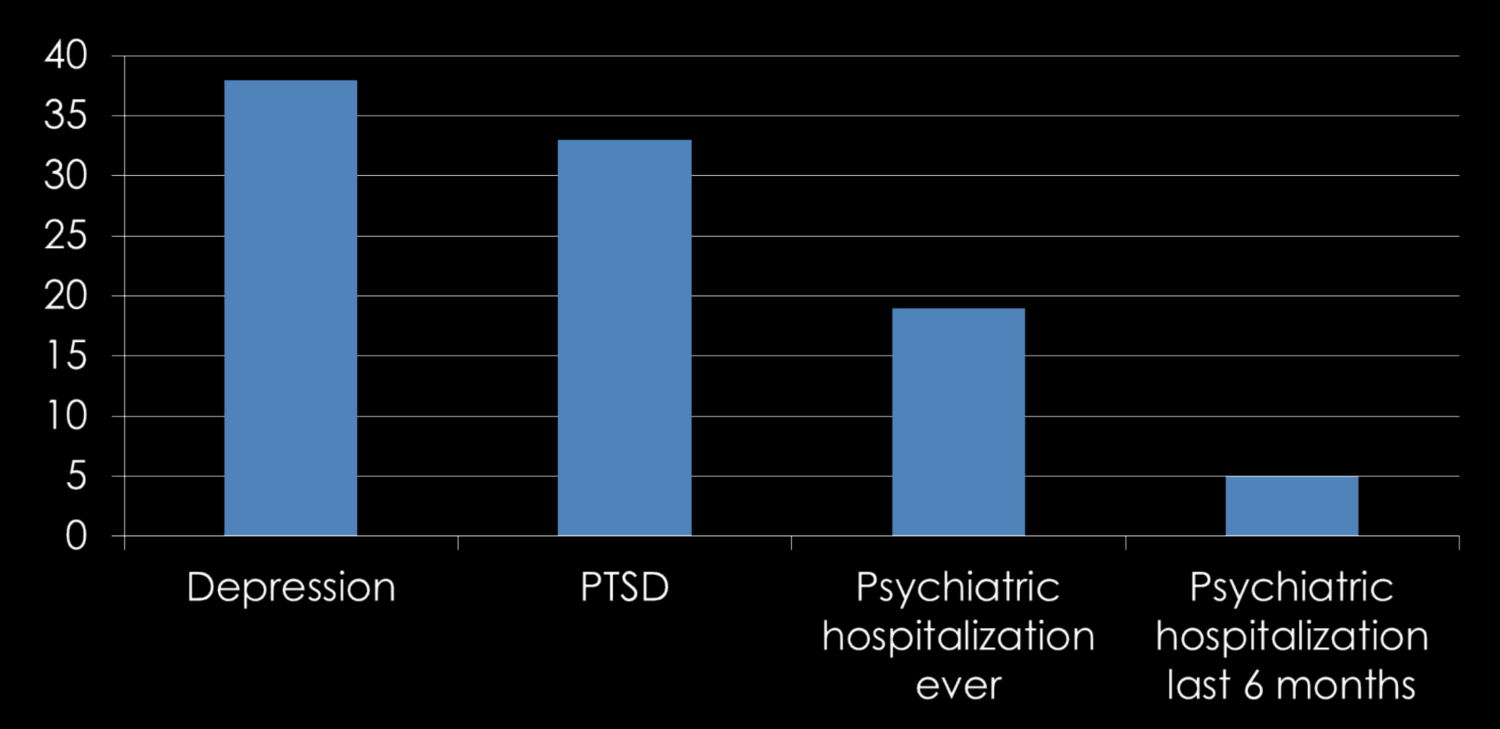

A chart shows the prevalence of mental health problems among participants in Kushel’s study of older homeless individuals in Oakland, CA (numbers are percentages). (Image courtesy of Margot Kushel.)

Many Americans live one paycheck away from street homelessness, and those most at risk may be older, according to new research presented at Massachusetts Institute of Technology Oct. 11 by Margot Kushel, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco.

In a talk at CASW’s New Horizons in Science (part of the national conference for science writers, ScienceWriters2015), Kushel explained that a staggering proportion of older people living on the streets—43 percent of older people she studied—first experienced homelessness at age 50 or later.

The loss of a job, the death of a spouse or even a stressful argument with a family member can lead to homelessness. And with that first night of living on the streets comes profound loss—of one’s health, belongings and sense of wellbeing, according to Kushel. In an already older population, homelessness ravages individual health. On the streets, Kushel said, “50 is the new 75.”

A clinician who has treated homeless patients at San Francisco General Hospital for two decades, Kushel shifted her focus to the older population when she realized that older people without homes were being admitted to hospitals suffering from a new constellation of ailments.“

A person with congestive heart failure, some dementia, who can’t see or hear well, who can’t walk that far—sending him back out on the street seemed like such an utter impossibility,” she said.

Kushel’s career both treating and studying those experiencing homelessness offered a dual perspective, leading her to recognize subtle changes in the homeless population.

“I can draw from what I’m seeing at clinical sites,” she said, “and then step back and ask the broader questions.”

A rapidly aging population

She thought the homeless population was aging and collected data that confirmed her hunch. The proportion of elderly among those without housing more than tripled between 1990 and 2003, according to Kushel, and the trend continues today.

But this data does not explain the events that might catapult someone onto the streets in their 50s, so Kushel began tracking the lives of 350 of Oakland’s older homeless residents. She found stories that speak to the harsh economic realities experienced by semi-skilled workers with little formal education.

Homelessness among the elderly is inescapably related to race and gender, Kushel explained. She said a disproportionate number of Oakland’s elderly homeless are African American, male and unmarried, pointing to the roles of systemic racism and social relationships among the cascade of events propelling someone toward homelessness.

Still, contrary to popular perceptions of the homeless, many of Kushel’s research participants maintain some contact with family and are rooted in their communities through churches, senior centers and organizations like Alcoholics Anonymous. The stereotype of homelessness arising from poor social connections does not quite hold up among the elderly, Kushel said.

Another stereotype that Kushel’s research is dismantling deals with the nature of mental health problems associated with homelessness.

“I would like to walk back from this image of homelessness as a problem of people with schizophrenia,” Kushel said, explaining that only 5 percent of participants in her study had been recently hospitalized to treat psychiatric conditions.

Much more widespread, and complicating, are severe cognitive impairments. And Kushel spoke of the quiet devastation of severe depression among more than a third of the elderly homeless. Depression, she said, was often brought on by homelessness and remaining without a home often made depression more difficult to address. In treating depression, the standard solution of controlling a patient’s environment is out of the question.

“It would be hard to design a worse milieu for someone who has mental health problems,” Kushel said. “Homelessness is Bizarro World.”

Family ties: hints of solutions

But seeds of solutions to the problem of homelessness lie among the intricacies Kushel discovered. The fact that many older homeless people are in touch with family is leading Kushel to investigate whether it might be possible to house them under the same roof as part of the national push for long-term supportive housing for the chronically homeless. Kushel said she is already seeing improvements in the mental health of study participants who have been re-housed. One such participant was nearly unrecognizable to Kushel, not just because he’d had a chance to shave and shower, but also because he was “walking with a bounce in his step, where he used to walk with his head down.”

Kushel said she came to study homelessness because it “really bothered my sense of social justice…It felt like we were wasting a lot of people’s lives.” As her research moves towards solutions, she reveals a blend of passion and practicality that can only help in addressing a problem that seems both intractable and ever-changing.“

I’m an advocate for homelessness to end,” she said, “but I am relatively agnostic to how it ends.”