Patients’ waste is this scientist’s treasure

A wastewater treatment plant in Hostivice, Czech Republic. (Wikimedia; 2009 photo released to the public domain by Jan Suchy)

A class of viruses once thought to cause disease could yield a novel cancer therapy.

A newsmaker from an unexpected encounter has offered scientific news from an unexpected source—poop.

As I looked for stories at a science writers’ conference in State College, Pa., it was the fellow student scientist who sat down next to me who provided a rich story about the potential for pathogens called reoviruses—commonly found in human and other animal waste—to advance the control of cancer cell growth.

“A lot of people who get infected with reovirus will get it and not even know it,” said Tarryn Bourhill, a PhD student cancer researcher at the University of Calgary. Bourhill has a passion to answer scientific questions and also shares an interest in science journalism, and this is why she was spending time out of the lab to attend the ScienceWriters2019 conference in late October 2019.

The reovirus family was identified decades ago, but it wasn’t until recently that scientists observed that reovirus can specifically target and kill cancer cells, leaving normal ones unscathed—a discovery bringing new meaning to the phrase “one man’s trash is another man’s treasure.”

Despite significant advances in treatment, cancer remains the second largest cause of death in the United States, according to the National Center for Health Statistics. In recent decades, government agencies, medical institutions, and pharmaceutical companies have spent billions of dollars exploring the biology of cancer and searching for innovative ways to kill drug-resistant cancer cells that elude the body’s immune system, grow uncontrolled, and spread to distant organs.

Many of the new immunotherapies have had limited success or have been time-consuming and costly, and some are still highly experimental, Bourhill notes.

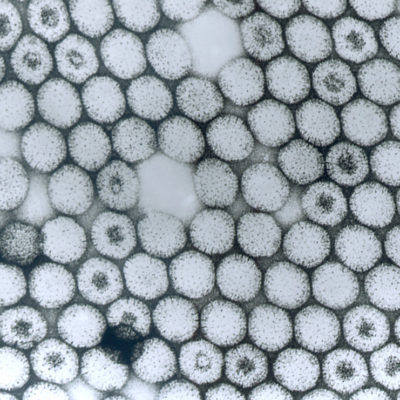

Bourhill’s research is tied to modern immunotherapeutic approaches, but also to a field of investigation whose origins date back to the 1950s, when reoviruses were identified in hospital patients’ stools and were suspected of causing disease. These chunky brown liquid samples were put into tubes and analyzed in labs. Scientists also took samples of sewage in wastewater plants to determine whether reovirus was detectable in the waste stream.

The reovirus family is named for the viruses’ target organs—respiratory (lungs), enteric (digestive tract)—and the fact that they are not associated with a specific disease (orphan). Reoviruses have been linked to some cases of diarrhea and are thought to contribute to the development of celiac disease, but generally a reovirus causes no symptoms in people who become infected.

Bourhill explains that over the years, in clinical trials, reoviruses have been shown to kill various cancer cells, including cells from colorectal, pancreatic, and gastric cancers. The bigger question that draws her interest is why does reovirus kill only these types of cells? “Most oncolytic viruses [viruses that kill cancer cells] that are in development or clinical trials have to be engineered to target cancer cells, but reovirus does that naturally,” she said.

To exploit this natural tendency, her current project in the lab of Randal N. Johnston is investigating why some types of cancer are sensitive to reovirus attack and why others are not. The secret may lie in the fact that cancer cells share certain properties of normal embryonic stem cells, such as the ability to regenerate. Bourhill is investigating whether these qualities are what make certain cancer cells more susceptible to reovirus infection.

“In the Johnston lab, we are interested in understanding why embryonic stem cell status in a tumor is what makes a cancer cell sensitive to infection,” Bourhill said. Embryonic stem cells share certain biological traits with cancer cells, and both activate similar genes. Understanding why “stemness” makes some cancer cells sensitive to reovirus will help scientists screen patients to determine whether a reoviral treatment might benefit them.