Russian aggression leaves Arctic science at risk

Sea ice coverage in the central Arctic has shrunk dramatically in recent decades. (Image from Alfred-Wegener-Institut/Mario Hoppmann (CC-BY 4.0))

Olga Shpak used to study whales in the Arctic Ocean. Now, she volunteers on the front lines of a war to defend her hometown of Kharkiv from Russian attacks. “My life has changed drastically on February 24th,” she said. “My priority is not science, not Arctic, not whales, but people.”

Shpak, a Ukrainian marine biologist formerly associated with the Severtsov Institute for Ecology and Evolution of the Russian Academy of Sciences, shared her experiences as a scientist affected by the ongoing Russia-Ukraine war. Her comments were part of a session about Arctic science and journalism without Russia on Oct. 24, part of the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing (CASW)’s New Horizons in Science briefings at the ScienceWriters2022 conference in Memphis, Tenn.

Shpak was joined by Markus Rex, head of atmospheric science for the Alfred Wegener Institute in Germany, and Andrea Pitzer, a journalist and author reporting on the Arctic and climate change, with moderator Rich Stone. Stone, senior science editor at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute Department of Science Education, recently visited Ukraine on a reporting trip for the journal Science. Together, they discussed the present and future of Arctic science — a key area of focus for climate change research — and the devastating impacts of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

A uniquely threatened shared resource

The Arctic, with plentiful resources including oil and fish and a uniquely valuable location for transportation and defense, has always been a site of conflicting geopolitical interests. Shpak explained that Arctic ecosystems are extremely fragile, more so than those in temperate zones, and there are populations of fish that move between areas controlled by different countries, such as the polar cod harvested by both Russia and Norway. Countries must collaborate and share data to avoid population depletion and ensure sustainable fishing, while keeping in mind Indigenous populations that also rely on these marine resources.

“No matter what the political situation is… the consequences for nature may be really bad if certain collaborations are not maintained,” Shpak said.

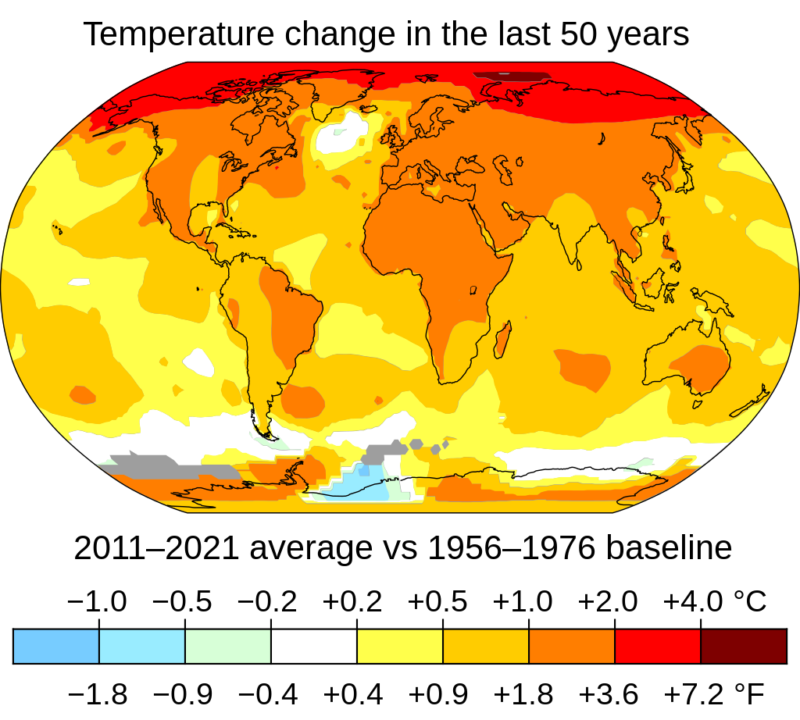

The Arctic is also crucial to the long-term future of Planet Earth and is one of the places where the effects of climate change are most dramatic. “You don’t need scientific data or sophisticated statistics to see climate change in the Arctic – you only need your eyes,” Rex said.

Pitzer mentioned that the Arctic is warming four times faster than lower latitudes. Rex noted that there are now only around 4 million square kilometers of Arctic sea ice, whereas there was over twice as much coverage — 8 million to 10 million square kilometers — in the 1950s to 1970s.

Unfortunately, what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic, and changes to this fragile region propagate to the middle latitudes where most people live. In the most pessimistic scenarios emerging from climate change models, surface air temperatures are expected to increase by 5 to 15 degrees Fahrenheit by the end of the century. Rex, one of the scientists trying to better understand the Arctic in hopes of learning more about the effects of climate change, recently led the largest expedition to the Arctic, MOSAiC. That expedition was partially supported by Russian supply vessels and icebreakers. Now, that collaboration is gone.

Little Arctic science possible without Russia

With over half of the Arctic coastline in its possession, Russia is a key collaborator in Arctic science. It is difficult, if not impossible, to do Arctic science or report on it without Russian data and cooperation to provide information on what’s happening in those frigid parts of the world.

Permits are necessary for journalists and scientists to visit the Arctic, and no Americans were granted those permits this year owing to the conflict. Travel to the central Arctic, key to Rex’s science, is currently impossible, as the route crosses through heavily militarized Russian-controlled territory.

Pitzer thinks this is only a taste of what’s to come as climate change exacerbates existing tensions, leading to further militarization and increased conflict in the Arctic. “Right now, you have a good guy and a bad guy. You have one country who invaded another and is doing horrific things there,” she said. “In the coming years, we’re going to see a lot of conflict in the high Arctic, and it’s not going to be as simple and clear who are the good guys and who are the bad guys.”

Scientists also struggle with the ethical dilemma of cooperating with a nation-state perpetrating such violence. “The attack of Russia on Ukraine made any further collaboration impossible,” Rex said, “and that is a tragedy. Above all, of course, it’s a tragedy for people. And it’s also a tragedy for science and for our ability to deal with climate change and protect our planet.”

Not only has the conflict stalled Arctic research and journalism, it has changed the landscape of Arctic science for years to come. Many Russian scientists have fled the country, and those remaining work in fear due to totalitarian restrictions on free speech, according to Shpak.

Russia had also been dependent on the West for equipment and lab supplies, Shpak said. Now, when something breaks, it may not be possible to acquire the parts to fix it. Chemicals and reagents for laboratories are in short supply.

Pitzer expects Russia’s increased militarization and aggression to influence collaborations — particularly who is willing to work with Russia — in the long term. “The longer this goes on, the longer that there are these barriers to working with each other, the worse this situation is going to be,” she said. “If the war continues, there won’t be anything left to collaborate with [in Russia] in a meaningful way.”

For now, scientists like Rex are continuing to work to protect the world from climate change using data they have already collected. All involved in this crucial area of study are striving to maintain personal ties and collaborations in the hope that the political situation in Russia changes soon, allowing them to resume their important work in the Arctic.

“Arctic warming does not wait. Climate warming does not wait. And the disappearance of the Arctic ice does not wait for humans to solve our political problems,” Rex said. “This tragedy has to stop. I don’t know how, but it has to stop as soon as possible.”