When science outpaces bioethics, public engagement can help

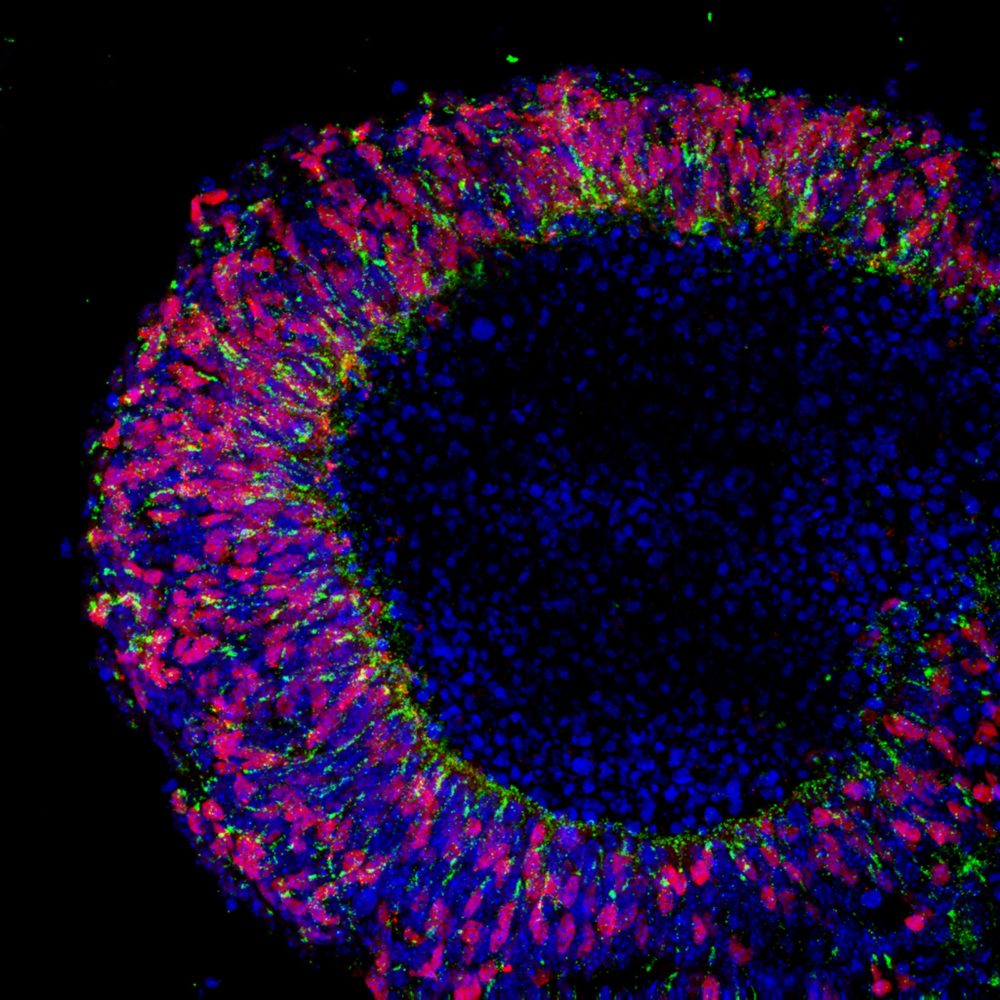

Fluorescence imaging shows a nascent retina (with the visual pigment rhodopsin glowing green and the transcription factor Crx glowing red), generated at University College London from embryonic stem cells, that could lead to a treatment for blindness. Bioethicists are calling for more public engagement in decisions regarding embryonic and stem cell research. (Image by Anai Gonzalez-Cordero on Flickr, CC BY-NC 2.0)

Researchers and ethicists call for new processes to bring public voices to bear on the “14-day rule,” other guidelines.

Embryos with both human and monkey cells. Mouse brains containing human stem cells. Synthetic embryos so convincing they fool pregnancy tests. These may sound like vignettes from the backstory of a sci-fi film, but they are just a handful of recent advances in embryonic and stem cell research that push scientific boundaries and raise new ethics questions.

What is the legal status of an embryo if it didn’t come from an egg and a sperm? What are the rights, if any, of an embryo that is part monkey and part human? What kinds of advances in medicine and biological research would make facing these questions worth it?

Amidst this slew of scientific developments and accompanying ethics issues, experts are calling for a reexamination of how guidelines and regulations for embryonic and stem cell research are made and asking the public to make their voices heard.

Speaking Oct. 4 at the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing’s Perlman Symposium during the virtual ScienceWriters2021 conference, University of Wisconsin bioethicist R. Alta Charo challenged the public to look beyond headlines about designer babies and instead ask “What are the less obvious controversies … the things that we could really do something about?”

One such topic is the 14-day rule, an international guideline that restricts human embryo research to the first two weeks after fertilization—beyond which the nervous system begins to develop. The rule was first proposed in 1979 by the Ethics Advisory Board of the then U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare. It became law in several countries, and in others like the U.S., it was adopted as a guideline in accordance with recommendations from domestic agencies and international bodies such as the nonprofit International Society for Stem Cell Research, or ISSCR.

At the time the rule was proposed, biologists lacked the technical capability to grow embryos for as long as 14 days outside of a uterus. But technological advances have since reached that threshold, resulting in calls for a revision of the rule. Further, a growing body of research suggests that the 14 to 28 days after fertilization could be crucial for understanding the development of Huntington’s and other diseases, and screening for drugs that might treat them.

The 14-day rule has limited many avenues of research, as molecular biologist Ali Brivanlou knows from personal experience. In 2016, the Rockefeller University embryology laboratory head and his team developed an embryo that could survive and develop outside of the uterus beyond two weeks, a feat no other lab had reported before that point. They discovered that tissues that could ultimately turn into various organs had begun to form even without maternal hormonal input. But in deference to the rule, they ended the experiment prematurely.

“It was one of the toughest decisions I have made in my life,” Brivanlou said. “To see the structures actually continuing to move forward—opening up windows to horizons I had never seen—and then having to stop it was very difficult.”

Since then the ISSCR has released new guidelines which, among other changes, revised their stance on the 14-day rule to allow a special review process for experiments that might take longer. The international panel that took 18 months to come up with the new guidelines included Charo, Brivanlou, and other scientists, clinicians, lawyers, and ethicists—but lacked a mechanism for public comment.

This approach contrasted starkly with that of the ethics board that proposed the 14-day rule in 1979. That group sent out thousands of public notices about their review process; held public hearings over three months in 11 major U.S. cities including New York, San Francisco, Kansas City, Denver, Dallas, and Atlanta; and devoted 20 pages of their report to outlining input received from the public. “Everyone who requested to appear was heard; 179 individuals presented testimony in hearings .… Eighteen people preferred to submit formal written testimony in lieu of oral presentation. In addition, the Board received over 2000 letters and postcards,” the report states.

Regarding the 2021 guideline revisions, Hank Greely of Stanford University’s Center for Biomedical Ethics said by email, “The ISSCR process led to some very useful guidelines with certainly a lot of expert scientific input, though I worry that they may not have taken into account a sufficiently wide scope of public views.”

Responding to this lack of engagement with general audiences, the Center for Genetics and Society, a nonprofit focused on the ethical use of genetic technologies, accused the stem cell research rule-making body of “building ‘consensus’ in an echo chamber,” saying they had failed to solicit public input or take into account the fact that the 14-day rule is the law in many global research hubs, including the U.K., China, and Japan.

Charo said the public can take a direct approach by electing representatives and voting on referenda in support of policies that reflect their ethics concerns. “In the end, it is up to all of us to answer these questions,” she said.

Other experts advocate for a formal ethics-focused mechanism for members of society to make their values known. That could be a national bioethics commission, some form of which existed from the Ford through the Obama administrations. Proponents recommend that the commission be made up of experts from a cross-section of fields such as law, ethics, and biology, and be tasked with researching bioethics issues, advising the U.S. president, and, specifically, engaging with the public through open hearings.

“Trust me that we really want to reconcile the scientific world with the ethical and moral, sociopolitical values in the society in which we operate,” Brivanlou said.