Native American communities battling COVID-19 draw on strengths

In his recorded remarks to ScienceWriters2020 attendees, Spero Manson, director of the Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the Colorado School of Public Health, urged journalists to avoid reinforcing victimhood stereotypes when reporting on the COVID-19 experience in Native American communities.

Media accounts that focus solely on health inequities overlook stories of strength within American Indian and Alaska Native communities and reinforce victimhood stereotypes.

From smallpox to COVID-19, introduced infectious diseases have had a disproportionate impact on Native American communities for centuries. The current pandemic is casting a harsh spotlight on the systemic contributors to this unequal burden.

But Spero Manson, a professor of public health and psychiatry at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, maintains that media accounts that focus exclusively on these inequities are overlooking stories of strength within American Indian and Alaska Native communities and reinforcing victimhood stereotypes.

Amid the challenges of reporting on the COVID-19 pandemic in minority communities, experts say context is the key to respectful coverage that doesn’t perpetuate harmful fallacies or oversimplifications.

In an Oct. 12 recorded video presentation to the virtual ScienceWriters2020 conference, Manson urged science journalists to draw on the lived experiences of peoples with a long history of persevering through pandemics in the past. Manson, who identifies as Pembina Chippewa, is director of the Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the Colorado School of Public Health.

Reporters “don’t actually pay equal attention to the sources of strength, resilience, and the solutions that are beginning to emerge at the local level,” Manson said in a subsequent interview. “And so we get painted with this sort of victimology.”

In his talk, part of the New Horizons in Science program organized by the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing, Manson laid out how the COVID-19 pandemic has had an outsized impact on Native American communities.

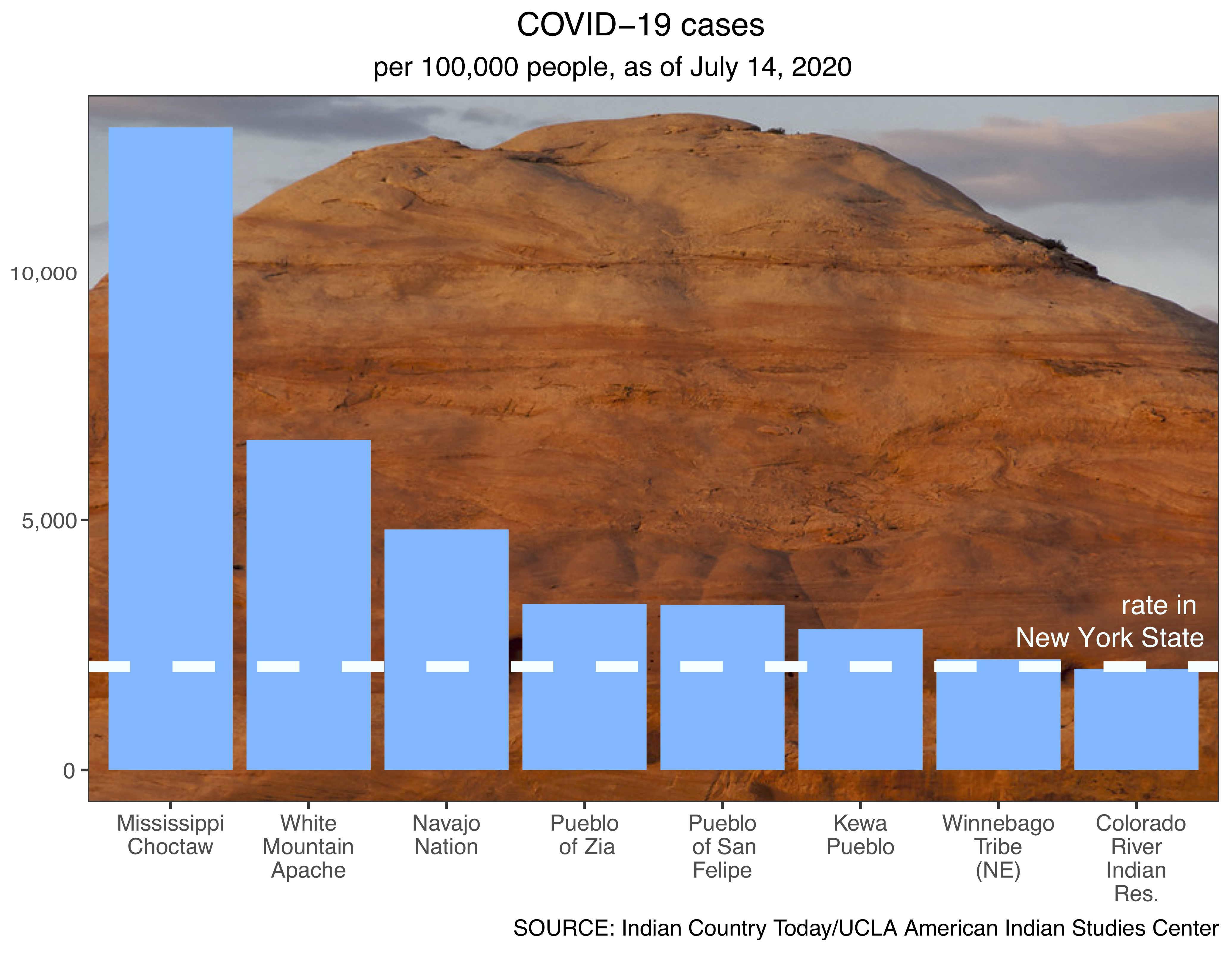

By mid-May in Arizona, American Indians comprised 18% of reported COVID-19-related deaths, despite accounting for only 4% of the state’s total population. Among the Diné of the Navajo Nation, the largest reservation in the United States, seven in every 100 people have tested positive for the virus—an infection rate higher than any state. According to a report by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, in the 23 states with reliable data, Native Americans were three and a half times more likely to have contracted the novel coronavirus than non-Hispanic white residents.

These disparities, according to Manson, spring from a variety of underlying causes. For instance, the federal Urban Indian Health Program is meant to provide healthcare for the 70% of Native Americans living in metropolitan areas, yet it only receives 1% of the total Indian Health Services budget. Additionally, a lack of access to running water in some communities can impede handwashing, crowded housing conditions can limit residents’ ability to socially distance, and a lack of access to transportation can restrict travel to COVID-19 testing facilities.

“Our traditions shine brightly”

Despite the challenges, Native American communities have drawn upon their resources, sovereignty, and cultural values to combat COVID-19. Tribal leaders in Alaska, for instance, restricted flights into their communities at the start of the outbreak, working with the full support of the local government to prevent an influx of infections.

Multiple communities have worked together to harvest medicinal plants that can treat symptoms of COVID-19. And Manson said Native American communities all over the country have rallied to support those most at risk from the virus, including a restaurant in Minneapolis that delivers traditional meals to homebound elders.

Eschewing harmful tropes when covering Native American health is the first step toward more accurate coverage, Manson said. He advises science writers to also recognize that American Indians are not one cohesive group or identity. For example, Manson said he identifies first as part of the Pembina Chippewa tribe but doesn’t always automatically think of himself as American Indian. “Native American,” in other words, covers a patchwork of identities, and problems and solutions can differ significantly depending on a person’s tribal affiliation or location.

In addition, Manson cautions science journalists against wanting “to immediately go to matters of spirituality and traditional healing ceremonies.” An outsized focus on these practices, he said, perpetuates stereotypes and ignores other aspects of Native American identity that are relevant to health in the modern world.

Throughout history, he said, American Indian and Alaska Native peoples have overcome daunting obstacles to persevere against diseases introduced from overseas. At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, Manson interviewed an Athabascan elder in Alaska who drew upon that historical tradition to describe his tribe’s view of the current fight. “Once more, darkness descends upon our people and this land,” the elder told Manson. “Today … a virus. Suffering and death always follow. Yet our traditions shine brightly, casting light to guide the way. We again struggle to survive, buoyed by these traditions, now armed as well with medicine and science, weapons of the Western world. The challenge is how to bring both to bear on this danger so we may live on.”