CASW Lifetime Fellow David Perlman hailed as he takes “early retirement”

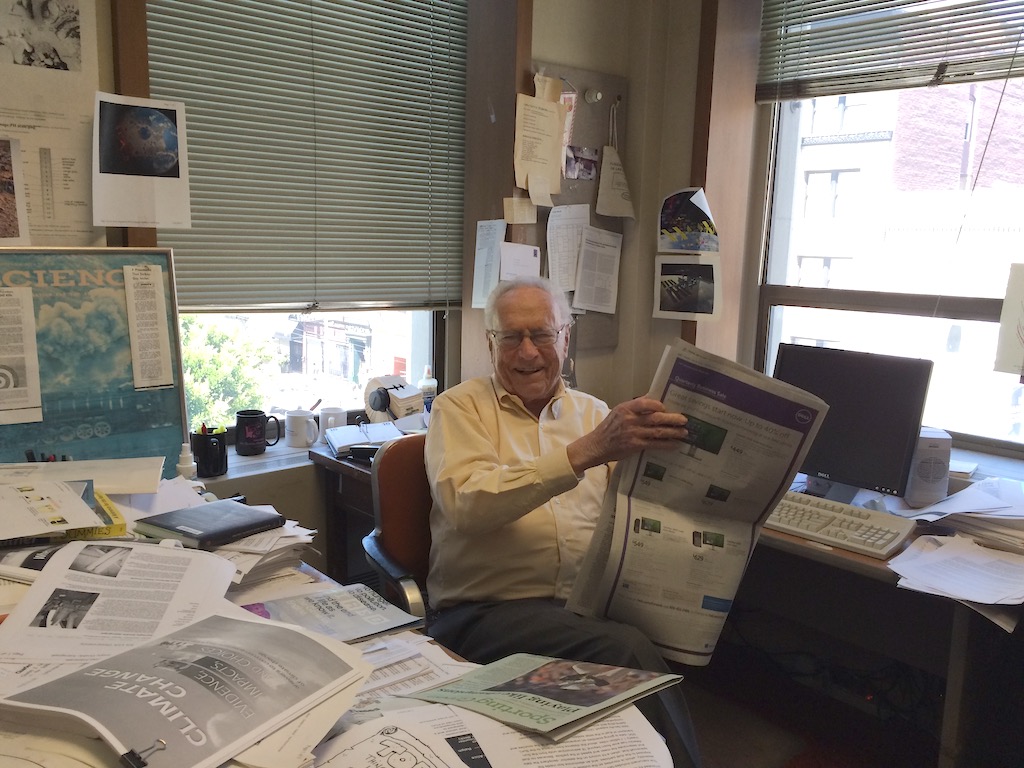

Perlman still at work in his Chronicle corner office in 2015. Photo: Rosalind Reid

After almost seven decades at The San Francisco Chronicle, former CASW President David Perlman will finally close his reporter’s notebook on August 4, retiring at the age of 98 after an accomplished career that made him a legend among science journalists. CASW colleagues took the occasion to recall some of their professional encounters over the years with the Dean of Science Journalism, who served as CASW’s vice president 1973-76 and president 1976-80. On his retirement from the board in 2011 after more than four decades of service, Perlman (shown at right talking with Charlie Petit in his office in 2015) was awarded the singular title Fellow of CASW.

Links to some of the coverage of Perlman’s retirement:

- Perlman told the Columbia Journalism Review the story of how he got started as a science journalist, and hints that there may be a memoir coming.

- In KQED Science, Craig Miller noted: “Perlman has churned out thousands of articles over the years. Not only has he won numerous science journalism awards, there are two named for him.”

- Perlman called cuts to newspaper science coverage “absolutely obscene” in an interview with Daniel Funke for the Poynter Institute website.

- On NPR’s Morning Edition, Steve Inskeep talked with Perlman about the public’s poor understanding of climate science and what the big science stories of the next 60 years might be.

Video

In an interview with CASW President Cristine Russell in April 2009, Perlman offered advice to aspiring science journalists.

WCSJ2017 travel fellowships honor Perlman

Seventeen Perlman Fellows from around the globe will travel to San Francisco in late October to attend the 10th World Conference of Science Journalists. The journalists’ travel grants are in honor of David Perlman and came about in part through his personal efforts to recruit sponsorships. Science writers pooled $40,000 in donations, and a foundation associated with San Francisco scientist/entrepreneur Bill Rutter added $25,000 to create the David Perlman Travel Fellowships.

Perlman’s career was celebrated in an announcement of the donation campaign at the WCSJ2017 website.

Tributes to a consummate journalist and generous colleague

Richard Harris, CASW treasurer

I grew up reading David Perlman’s pearly prose and was often inspired by it. When I worked as a copy boy at the Chronicle during high school, I remember reading the clips from Dave’s trip to the Galápagos Islands. The dispatches sounded like the serialized adventures of Richard Halliburton (it’s worth looking up his Royal Road to Romance if this name doesn’t ring a bell. Halliburton swam the Panama Canal and paid a toll of 36 cents).

I still remember a lede Dave wrote in the late 1970s. This is not an exact quote, but it captures the essence of a man who knew how to guide the public into the world of science. It read like this: “It’s time to learn a new word: teratogenic.” Dave knew that the word was unfamiliar, yet he also knew that it was time to add it to our collective vocabulary. To me, that reflected not just an eye for what’s important in science, but an astute ear for knowing where to meet his readers.

There’s one Perlman anecdote I often tell to young science writers: At press conferences, Dave would often stand up and say, “Let me see if I have this straight. You are saying…” and he would proceed to paraphrase what the scientist had just said. It was the perfect way to test his understanding of the subject (which was of course usually right on the mark), while also helping an audience of reporters, who were often too self-conscious to ask the “dumb question,” understand what had just been said. I have used that technique throughout my career and I have no doubt it has saved me from many blunders.

I worked at the San Francisco Examiner in the early 1980s while Dave (and Charlie Petit) were across the composing room at the Chronicle. There could be no more humbling and inspiring way to learn the ropes of daily science journalism. It was a tutorial like none other. And for that I am grateful beyond words.

Charlie Petit, CASW secretary and Chronicle colleague

While working alongside Dave Perlman for 26 years at the Chronicle, he amazed me the whole time with his rock-solid integrity. He believes in truth, fairness, the power of the press, decent grammar, a good lede, and the courage to confront fools and the confusion they sow. Science is his beat, but for decades upon decades to be a plain old newsman has always been his prime justification for rising each morning. He is kind, generous, good-humored, and armed with a vast skein of friends and colleagues. He has anecdotes and wisdom for all occasions. He is a cherished part of my life as mentor, hero, and pal.

In the late 1970s Dave, the old lefty, was elevated to management as city editor at the Chron with its vigorous Newspaper Guild union. He was a great city editor through some horrific, demanding news events such as the Jonestown murders and the assassinations of Harvey Milk and SF mayor George Moscone. I became lead science correspondent. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab lured me and lot of other reporters to Pasadena for a big planetary mission’s landing or orbital rendezvous. I think it was the Galileo flyby of Jupiter.

Dave couldn’t stand staying at the office. He soon joined me in the press room and associated events just to be there. He promptly filed a story from, I think, a gathering of big shots like Carl Sagan ruminating on human destiny in space or something else grand.

And that is why one of the subsequent yarns filed to the Chron from the mission got falsely run under my byline. Dave just couldn’t help himself. Reporting is what he does.

Cristine Russell, CASW president 2006-13 and longtime board member

In college, as a biology major and reporter for the weekly newspaper, I decided I would rather write about science than do it. But how? The answer came from David Perlman, who I cold-called and asked to visit at the San Francisco Chronicle. His fascinating stories of covering science, from local to exotic, not to mention his charm, convinced me that this indeed was the way to go. Besides, he had an office (little did I know that this was the exception to the rule). Amazingly, five years later, as a Washington Star reporter, I found myself working alongside David at the extraordinary Asilomar Conference, learning firsthand how the “dean” asks the right questions and later comes up with a great story on the science and ethics of recombinant DNA research.

Other similar experiences with David followed, from covering the Mars landing from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena to annual American Association for the Advancement of Science meetings around the country. Over the decades, I repeatedly saw David talking to young reporters or speaking to science journalism students—the ultimate mentor.

I once interviewed David about how he got into science writing after covering the world at large. He started as a Sputnik reporter, pushed quickly into action after the Russians launched the first artificial satellite on October 4, 1957, triggering the Space Race. He had to start from scratch with the most basic “how” and “why” reporter’s questions: How do you launch a small metal sphere into orbit around the Earth, and why doesn’t it just fall from the sky? Basic questions = great science writing for the general public. There’s never been a newspaper science reporter as in love with his craft—or as good at it—as David. To be honest, on occasion he can be a little brusque. I can already hear him grumbling, as he reads this, about too much praise.

Ben Patrusky, CASW Director Emeritus

[From remarks penned for David Perlman’s 95th birthday.]

There was B.D. (Before Dave) and A.D. I don’t remember much about B.D. If I were to guess, it was sometime in the late ‘60s or early ‘70s. But there is simply no getting back there, back past the singularity of the man, blinded as I was—and remain to this day—by the Perlman Big Bang. Suddenly there Dave was in my life, as if he had always been and there’s no recalling much before that, nothing about how and where we first met. And Big Bang it was, for Dave, big-hearted, generous, and encouraging mentor and friend (as to so many) opened up new worlds to me. It was not long after he exploded into my life, for instance, that I got a call out of the blue from a representative of the Weizmann Institute of Science inviting me to spend time as a visiting science writer. How on earth had the Weizmann found me? I asked. Dave Perlman’s recommendation, I was told. I was quite surprised for, as I recall, I’d hardly met the man and had no idea how and what he knew of me or my work. But I have been ever grateful, for that excursion to Israel proved pivotal to my career, and one of the most memorable adventures of my life.

There were so many more instances of extraordinary kindness and wise counsel to come, many having to do with Dave being one of my bosses during his decades-long tenure as a board member of the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing and mine as CASW’s program/executive director. I can’t begin to imagine how things might have been but for Dave’s eternal presence and glow.

(Apologies to Dave, if he finds this a bit over the top, knowing how much he eschews anything that smacks of gushiness, but as he’s been known to admonish others, especially when on deadline, “Don’t think, write,” and—you know what?—as they say, facts are facts.)

Joann Rodgers, CASW president 1989-97 and longtime board member

Many DP stories come to mind, but one that stands out—if an aging memory still serves me well—took place at a New Horizons in Science meeting at Stanford University in 1979. This particular meeting featured a presentation by Sidney Drell of the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center on what Ben Patrusky and Jerry Bishop (the program’s CASW organizers) had billed as a report on “nature’s basic blueprint” for the universe. It also featured Gordon Lasher of IBM presenting on models of the Big Bang long before a television program made it nerdy/cool to know or care about such things. Certainly I didn’t.

I rarely was assigned to write about physics and cosmology, having spent most of my years since joining the Hearst Newspapers in 1965 reporting about the biological sciences and medicine. To put it mildly, I was far more at ease with the vocabulary and presentations of Lee Hood and Hugh McDevitt, also presenters at the 1979 get-together. My plan, therefore, was to be a good soldier for my editors, show up at the Drell lecture, hope to understand enough to write down a note or two, and maybe find 350 coherent words to file.

Now David, unlike some of the notable science writers in our craft, never “school-marmed” newbies like me. But somehow he found his way to a seat near a bunch of us who weren’t “regulars” on the astrophysics beat, and who would struggle to make news out of Drell’s 90-minute oration and lengthy Q&A. David’s was a New Yorker’s subtle and unspoken “come with” offer, and he showed himself that day to be the best physics-whisperer I’ve ever encountered, sharing his left-handed, almost italicized “keyword” notes and asking the kind of generous questions of Drell that helped neophytes find the news peg rather than impress his more knowledgeable peers.

Over many years, I would come to learn many grand things about David. That never was heard a discouraging or impatient word from his calm voice. That he loved to lampoon Luddites and laugh out loud. That he was quick to share a knowledgeable love of Paris and poems and operas and all other high arts with anyone who cared to open a conversation and learn from him. That “sure!” he could, on one day’s notice, cadge four tickets to an “absolutely sold out” SF orchestra performance. With one phone call.

But David’s hallmark “constant” was asking those crystalline questions at press conferences and being willing, and even eager, to pose them in such a way that others—even his competitors—would get the lede, too. I don’t know anyone in four or five generations of science writers who didn’t benefit.

Astrophysics aside, David was equally at home reporting the biological and medical sciences that mattered most to me and consumed most of my career. Nearly a decade after that Stanford meeting, when I had left daily journalism and columnizing at Hearst for Johns Hopkins Medicine and book writing, David’s HIV and AIDS reporting was still serving as must-reads for not only a new generation of reporters, but also clinicians struggling to treat those terrible infections. The late great Frank Polk, who in the early ‘80s would establish one of the first dedicated East Coast clinics (at Hopkins) for people with HIV and AIDS, would frequently refer journalists who interviewed him to David Perlman’s San Francisco Chronicle stories. And whenever I showed up at Polk’s office or clinic to get the latest from him, he offered me the same good advice. Proud to say I took it.