Neurological complications of COVID-19 can persist for three months or more

Neurological symptoms following viral infections can be extensive and long-lasting, Dr. Avindra Nath explained as he shared with science writers what is known about Long COVID in a presentation at ScienceWriters2021.

Like other coronaviruses, SARS-CoV-2 can attack the brain, with consequences that can be devastating.

Coronaviruses and brain and nervous system disorders go hand in glove, says Dr. Avindra Nath, senior investigator and clinical director of the U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

“In general, all coronavirus that causes infection cause neurological complications. The depth and breadth of infections are underestimated. Almost all pandemic infections affect the brain, but it’s never been quite realized until much later,” Nath said, speaking on “What We Know about Long COVID: How Many Have Yet to Fully Recover and Why” Sept. 30 as part of the Council for the Advancement of Science Writers’ New Horizons in Science briefings at the virtual ScienceWriters2021 conference.

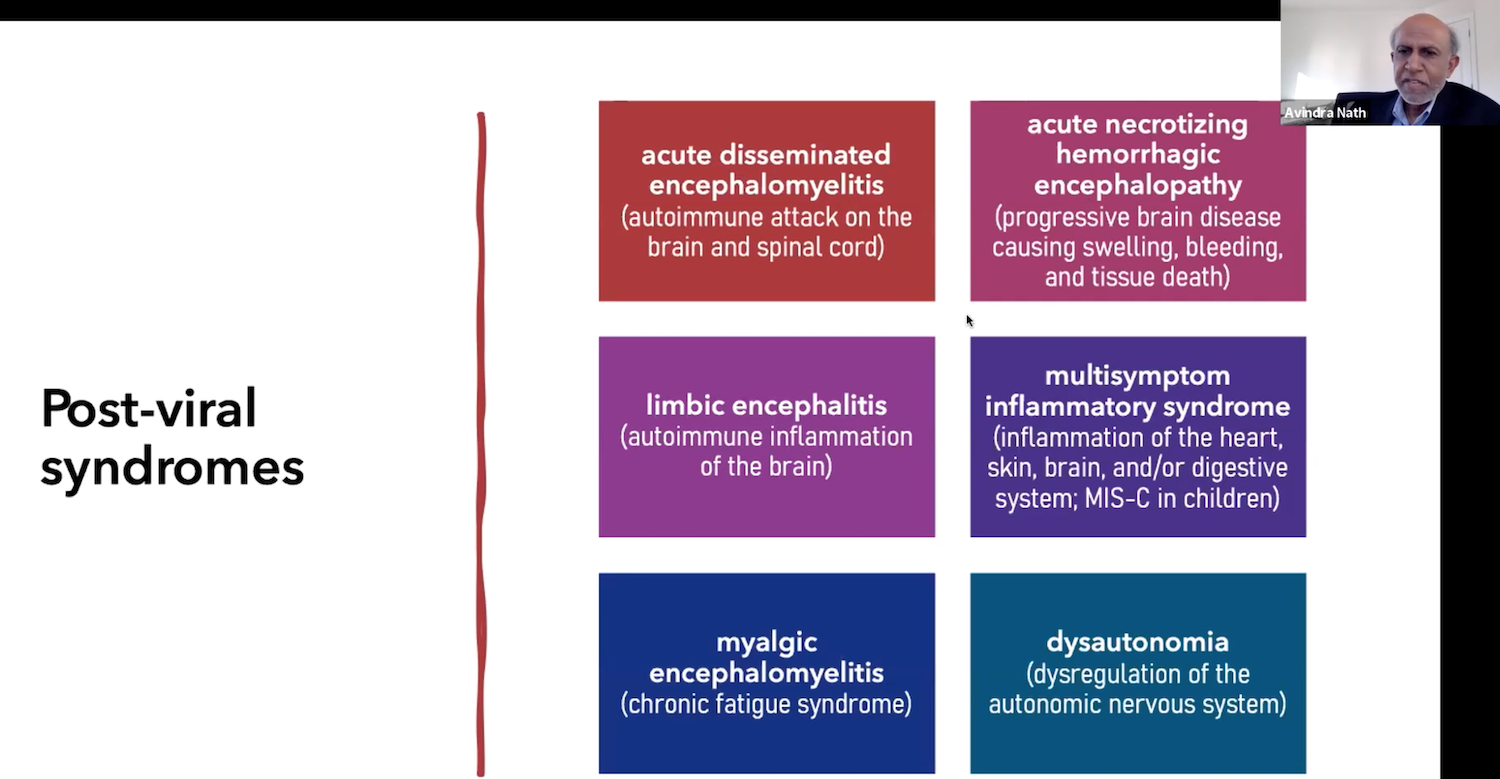

According to Nath’s slide presentation, post-viral neurological complications can persist three to four months and include brain swelling, lesions and injury, multisystem inflammatory syndrome, autonomic nerve system damage, and chronic fatigue syndrome. Immune system responses, loss of smell, encephalopathy, seizures, brain disease, and respiratory distress rank among cerebral complications.

“Almost 80 percent of patients lose their sense of smell. Sixty percent have some loss of smell they’re unaware of. This goes along with lack of taste. [The symptoms are] almost all immune-mediated,” Nath explained.

“There are patients who present with multiple strokes at the same time. There’s a thrombotic manifestation occurring in these patients. Some will develop a totally different type: micro hemorrhage,” he added.

Nath called “pretty dangerous” the consequences of the virus entering the nose and lodging in the brainstem. The Pre-Bötzinger complex—a cluster of neurons in the brainstem that is essential to maintaining breathing rhythm—can be “very sensitive” to changes in carbon dioxide levels caused by transfection of the virus.

“Patients don’t respond to changes in CO2. If they don’t remember to breathe, they’ll die. They usually die while sleeping,” he said.

Long-haul neurological symptoms include exercise intolerance, cognitive, mood, sleep disorders, pain symptoms, heart, blood pressure and breathing problems and loss of bladder control. A blood circulation disorder that causes the heart to race when a patient moves from a horizontal to standing position can also result.

“About 20 percent of people have dizziness. A subgroup has vertigo. Once the inner ear gets involved, you can get tinnitus. In hospitalized patients, nearly one-quarter had ringing in the ear,” Nath said.

Studies from the U.K. and Netherlands indicate a narrow window for treatment of these symptoms, which present more frequently in women than men. “Once you get past three to four months, if you don’t get better, it persists forever,” Nath said.

There have been a few reports of strokes in patients receiving the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, but overall Nath called neurological complications from COVID-19 vaccines “rare” and immune-mediated symptoms “treatable.”