Bad indoor air lasted weeks after Colorado fire

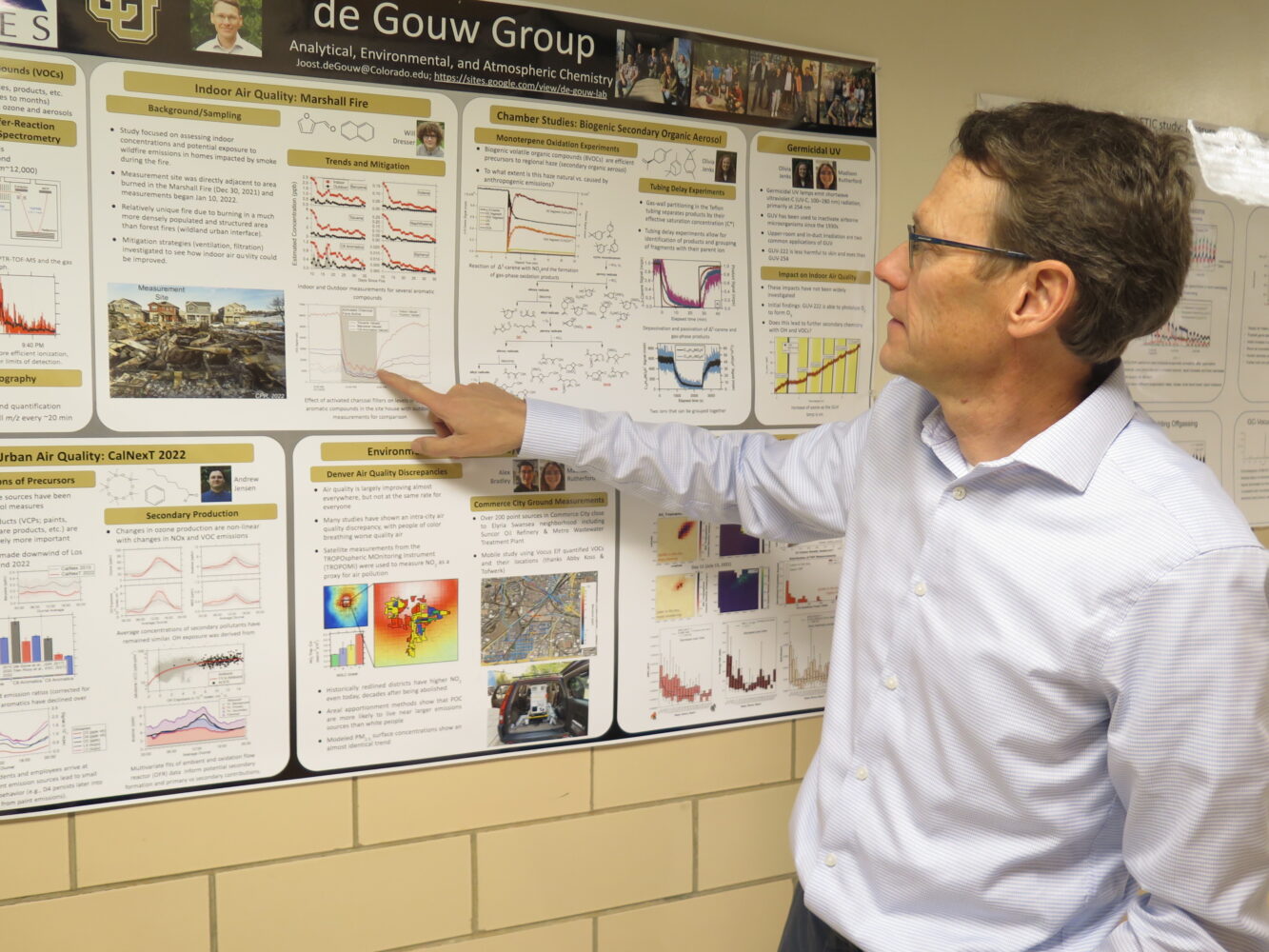

Joost de Gouw (facing camera) outside one of the homes where indoor air pollution measurements were taken after the 2021 Marshall fire in Boulder, Colo. (Photo by Christine Wiedinmyer)

After the most destructive wildfire in Colorado history burned more than a thousand structures, contaminated indoor air plagued surviving homes for several weeks. As the smell of smoke persisted even in newer homes, air quality researchers took the opportunity to answer an important question: What kind of indoor air pollution do wildfires leave behind?

They discovered a mix of smelly, sooty residues and elevated levels of certain toxic gases, findings that led to practical recommendations for homeowners reclaiming their properties after a wildfire. Joost de Gouw, a fellow at the University of Colorado Boulder’s Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences, described the work Oct. 9 during the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing’s New Horizons in Science briefings at the ScienceWriters2023 conference, held on the university campus. (A video recording of the session is available.)

The Marshall fire started in tall grass from an especially wet spring followed by a very dry fall and was spurred on by wind gusts up to 115 miles per hour. It destroyed an estimated 1,084 structures, including houses, a hotel, and at least one shopping center. Two people were killed. Blowing smoke from the fire caused immediate and lingering concentrations of contaminants inside surviving homes.

The fire started east of Boulder on December 30, 2021 and quickly moved into the cities of Lewisville and Superior, finally being doused by a snowfall on New Year’s Eve. De Gouw showed a map of the ignition point and the fire’s spread. “It’s really only maybe a mile and a half from here,” he said.

Surviving houses were new and very modern but now had interiors covered in ash and soot. Because of their expertise in air quality monitoring, de Gouw, colleagues at the university, and staff from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration were in an ideal position to study the effects of the fire on indoor air. But they had their doubts about the propriety of doing so after such devastating losses to the community.

In reality, homeowners were very receptive to having experts come inside their homes, set up measuring instruments, and inform them about the condition of the indoor air, which de Gouw described as smelling “like a campfire.” He said residents reached out to the experts because they wanted to know what the pollutants were, what they were smelling, whether it was toxic, how to clean it up, and if it was safe to return.

When the researchers checked levels of fine particulates, the indoor air actually qualified as “very clean air,” de Gouw said. But when professional cleaners came in to remove ash and soot from surfaces, wiping the walls and running vacuum cleaners, particulates in the air rose to unacceptable levels. ”You have to try and limit this as much as you can by wet cleaning, by using HEPA vacuum cleaners. But it’s also important to protect yourself when you do this, so wear a mask,” he advised.

Contrary to de Gouw’s initial assumption that volatile organic compounds (VOCs) would dissipate in a few hours, they lingered inside homes for up to six weeks. One of the compounds, benzene, is a known carcinogen. Fortunately, he said, one can build a high-capacity air cleaner using a box fan and furnace filters with an activated charcoal coating for about $80, ”and we found that they’re incredibly effective.” Homeowners had to keep running the filters because VOCs continued to outgas from reservoirs of contamination.

It would be difficult to correlate actual health risks with any particular measurements, but people did report headaches, nosebleeds, and more. De Gouw said longer-term studies will be needed to look at more chronic conditions, including incident cancers.