Fighting climate change with science (and poetry)

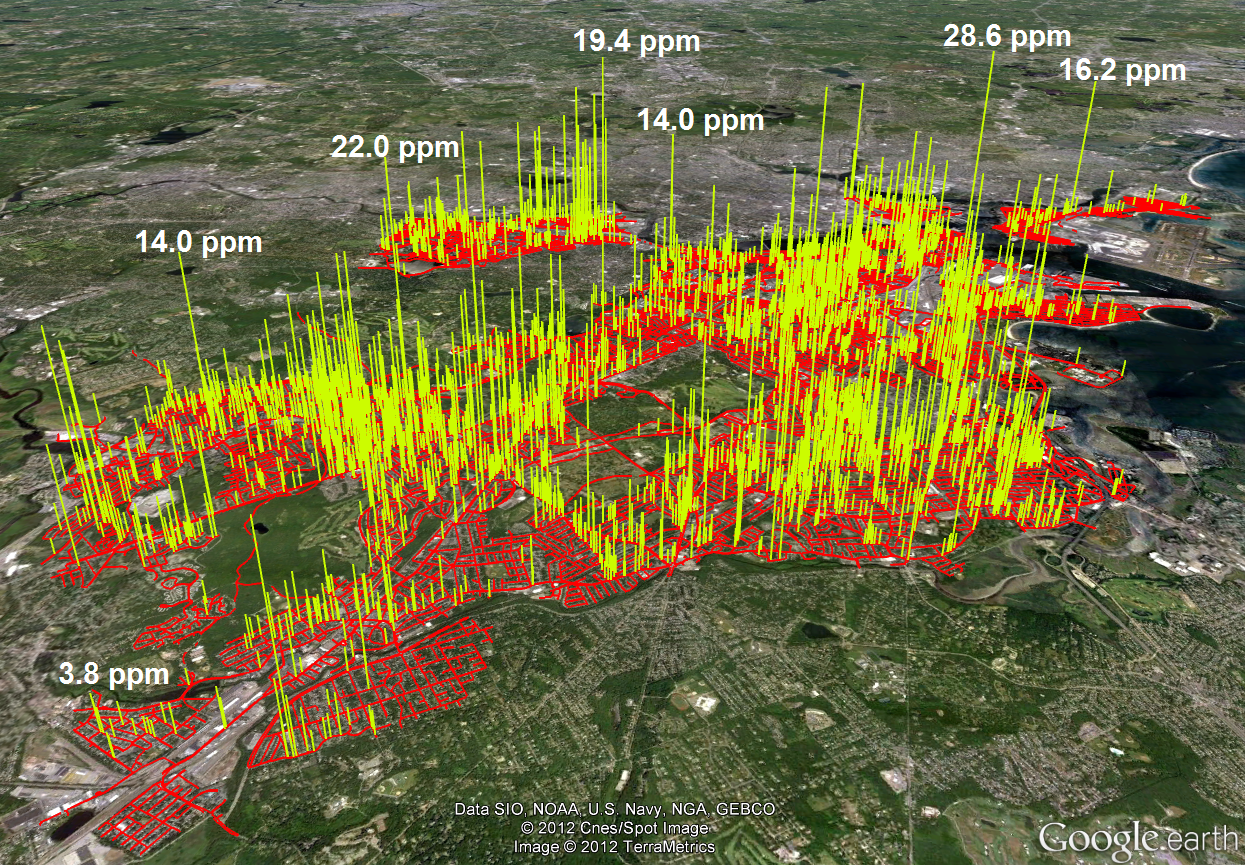

Methane leaks (yellow spikes) mapped on Boston’s 785 road miles. Image from Phillips, N. G., R. Ackley, E. R. Crosson, A. Down, L. R. Hutyra, M. Brondfield, J. D. Karr, K. Zhao, R. B. Jackson. 2013. Mapping urban pipeline leaks: methane leaks across Boston. Environmental Pollution 173:1-4.

An interview with Rob Jackson

Seven years ago, Rob Jackson and his graduate student drove around the city of Boston—back and forth, back and forth, up and down every block like a lawnmower. With a laser instrument in tow, the scientists mapped more than 3,000 natural gas leaks. This collaborative effort, involving Jackson’s Duke University team and a Boston University group led by Nathan Phillips, produced the first public map showing natural gas leaks in a city.

Two years later, the Massachusetts legislature passed a safety bill that included accelerated natural gas pipeline replacements and faster cost recovery for utility companies. It was a win-win.

This is one of the success stories that Jackson, now professor of earth system science at Stanford University, can claim for his research. He spoke Oct. 28 on climate change problems and solutions during a New Horizons in Science session organized by the Council for the Advancement of Science Writers at the ScienceWriters 2019 conference, and sat down to talk about his career.

A graduate of Rice University with a bachelor’s in chemical engineering, Jackson began his career as a scientist at Dow Chemical Co. While there, however, he began to wonder about ecology and the environment, subjects he was always interested in but had never formally studied. After taking night classes and trying out field work, Jackson decided to leave Dow for an ecology graduate program at Utah State. From there, a U.S. Department of Energy fellowship led him to a postdoctoral opportunity working on growing a natural ecosystem under high carbon dioxide.

“That was really the point in my career where I began to think seriously about climate and global change, an arc that has continued throughout my work today,” said Jackson, who now leads the Global Carbon Project of Future Earth, an international organization of scientists working on global sustainability issues.

The urgency of reversing climate change

Jackson’s talk, “Clearing the Air on Global Climate and Greenhouse Gases,” sought to answer three questions: Is the Earth warming? Do human actions affect the climate? And most important, what can people do about it?

He began by walking the audience through a series of slides with alarming statistics:

- The Paris Agreement aspires to keep the average global atmospheric temperature from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. It has already risen 1.1 degrees.

- 2014, 2015, and 2016 are the hottest years on record. The Earth is absolutely, unequivocably warming.

- Climate change isn’t about our grandchildren; it is happening now. Humans may be on the brink of melting the North Pole within a human lifetime.

- It’s not just about the rising temperature, but the disasters caused by extreme temperatures. Over $300 billion was spent on fires, droughts, and floods in the U.S. in 2017.

Humans’ influence on climate, Jackson said, has been known for nearly two centuries. “The fundamental physics of how the Earth works is actually quite simple.”

Essentially, he explained, the part of the sun’s radiation that falls within the visible light range passes easily through the atmosphere. About half of this energy is absorbed (taken up) by the Earth’s surface, but some of it will be emitted (given off) in a weaker form of radiation, infrared radiation. Greenhouses gases in the atmosphere, such as carbon dioxide and methane, will absorb this infrared radiation and then emit it in all directions, warming the surface of the earth.

The role of science in climate policy

The concept of global warming may be simple, Jackson said, but solutions will require the cooperation of scientists, policymakers, and society.

Jackson designed his lab to have two focuses, both of which involve climate change. Half the lab members work with the Global Carbon Project to directly study, measure, and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. They study oil and gas well pads, homes, natural wetlands, and city streets that contain a pipeline.

“I first and foremost want to use data to understand how systems work, natural and human, but I also want to use data to change the way systems work, particularly human systems,” said Jackson.

The other half of the lab focuses more on ecology, looking at effects of a changing climate on forest and grasslands. For instance, a recent study used satellites to understand the record drought that began in Texas almost 10 years ago. This work examined the dying tree canopy, pixel by pixel, and identified thresholds of hot temperatures and droughts where the mortality occurred. It also showed that in climate models, such record droughts will become more common in 50 years.

“My group tries to understand how events today provide clues for how the Earth will look 25, 50, or 100 years from now,” Jackson said.

When working with policymakers, Jackson cautioned, it is important that scientists remember that science is not the only variable they have to consider.

“I think sometimes where scientists go astray is when we say, here is a problem we’ve identified—whether it be climate, or water, or air pollution—and therefore society must do something about it. That’s no longer science,” Jackson said. “It’s up to voters, and society as a whole.”

Communicating climate change

Over the past few decades, Jackson said he’s aimed to improve his ability to communicate science to governments and members of the public, often working with communications professionals. “I’m happy to help anybody on any story, and I have tremendous gratitude for what science writers do,” he said.

He has also published two books of children’s poems, as well as poetry in several literary journals.

“I don’t necessarily think that poetry makes me a better scientist, but it makes me think about words differently,” Jackson said. “There’s a vocabulary that’s common in the scientific world that we forget isn’t normal—long words, lots of graphs—but I think science communication is all about remembering that science isn’t normal.”