How much safer is abortion than staying pregnant in the post-Dobbs era?

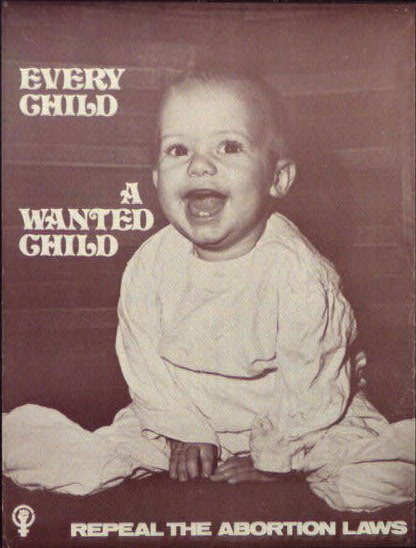

Abortion restrictions in the U.S. have gone through historical cycles of tightening and loosening as cultural, political, and legal wars have waged. This poster issued by the women’s liberation movement in 1965 called for repeal of laws restricting abortion. Many of those restrictionss were struck down by the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade decision in 1973 but are now being imposed again. (Image from the Library of Congress Yanker poster collection)

Thanks to a lack of health information related to abortion in the United States, scientists are uncertain just how much safer it is to carry a pregnancy to term versus having an abortion, since the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent Dobbs decision.

During an Oct. 7 session that was part of the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing’s annual New Horizons briefings for science writers in Boulder, Colo., sociologist Amanda Stevenson, a team member of the Colorado Fertility Project, and nurse practitioner and social scientist Kate Coleman-Minahan of the University of Colorado School of Nursing shared an up-to-date academic study on abortion and contraception in the post-Dobbs era.

Their work addressed the health impacts of banning abortion and contraception, as well as the specific needs and experiences of young people. They aimed to address a crucial question: Given all the factors at play, how much safer is abortion compared to carrying a pregnancy to term?

According to Stevenson, there is minimal health surveillance of abortion in the United States, rendering most of the data provided by the CDC “problematically” inaccurate. “Because the nation cannot consistently agree on the best method for measuring abortion incidence in the United States,” she told science writers, “it is extremely challenging to predict how we [might] observe changes, incidents, or consequences resulting from the restrictions on abortion and contraception.” In fact, the most recent national survey of abortion clients was conducted in 2014, nearly a decade ago.

With states increasingly imposing restrictions, Americans who can become pregnant have and will continue to travel across state lines in search of assistance, placing more strain on states that offer safe and legal abortion services. Coleman-Minahan’s research predicts these state laws will heavily impact young people. In her interviews, individuals 15-22 (from Colorado, California, and Texas) who considered abortion said that they face criticism in their decision-making process, receive little social support, and experience added burdens.

Stevenson said gaps in health-care monitoring make it impossible to answer questions that are important for comparing abortion risks with the risks of continuing to carry a pregnancy. These questions include how likely someone is to stay pregnant, to miscarry, or to die of a complication of pregnancy.“If you compare the relative safety of abortion versus staying pregnant,” she said, “most of the time you have to compare abortion to childbirth. But the counterfactual of having an abortion is not childbirth.”

Most important, Stevenson found that the inadequacy of healthcare services and the hinderances posed by state laws in the wake of the Dobbs decision, will make pregnancy more dangerous.

In a joint research project, Stevenson and Coleman-Minahan examined “near-death experiences or near misses,” severe consequences that impact people who are pregnant and their families and children. They used 2020 data to estimate how many people will experience severe maternal morbidity if unable to get an abortion. If 80% of denied abortions yield deliveries, their analysis suggests that after the first year, a full ban on abortion could result in an additional 1,000 people nearly dying every year.

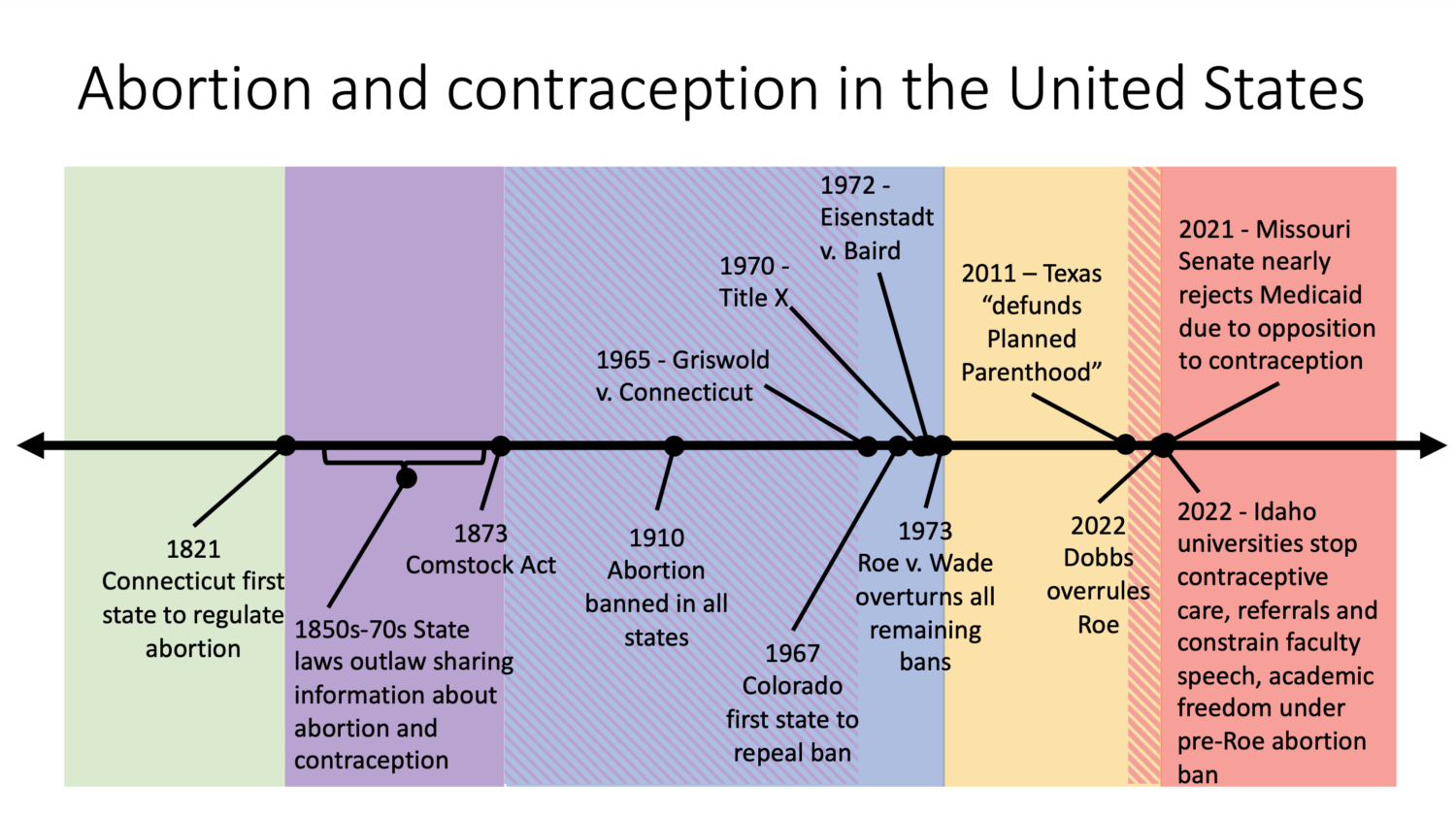

For the majority of the nation, the Dobbs ruling came as a shock. However, for those who have been studying abortion and contraception, it was not unexpected. Stevenson said, “It wasn’t surprising, because of the escalating set of restrictions that have been implemented since 1973, when the right to abortion was granted by the court’s ruling in Roe v. Wade.” Roe, she said, “was also expected due to the historical cycles of restriction and loosening of restrictions in the United States, concerning abortion and contraception. Abortion and contraception are consistently intertwined.”

From the Supreme Court cases and the initiation of the Comstock laws for contraception and then abortion, to the legalization of contraception in the United States in the 1980s, the parallel processes continue to escalate in severity with teenagers, people who have public insurance, and people with less autonomy.

Looking toward the future, Stevenson anticipates that contraception will be highly significant as a cultural and legal topic of debate. “Contraception violates exactly the same feminine norms associated with the same stigmatized or even damaging practices as abortion,” she said. “It violates the rule of perpetual accountability. It violates the norm of inevitable motherhood, and it violates the norm of instinctive nurturing.”