Leaders describe public health trust-building among Colorado Indigenous communities

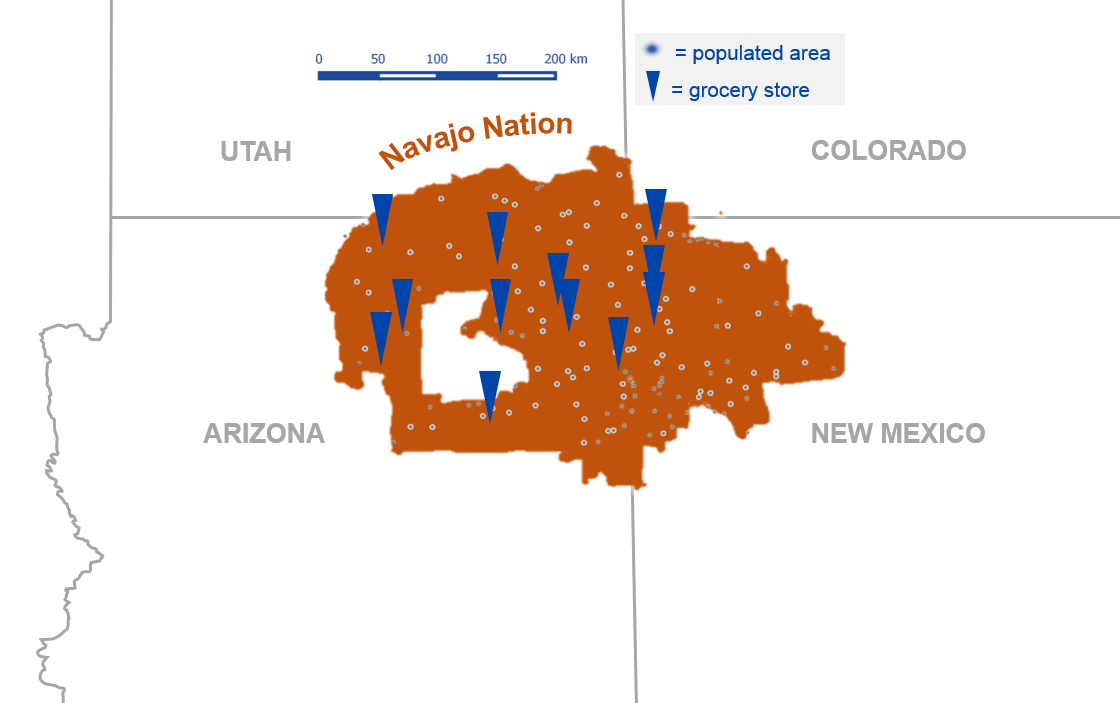

Grocery stores (triangles) are sparse in the Navajo Nation, which spans parts of Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico. Populated areas are indicated by dots. Original illustration by Taylor Tibbs.

In 2021, as new vaccines were spreading unevenly across the United States, the fastest and broadest uptake came in a population that had been especially hard hit during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic: the country’s Indigenous communities.

Lucille Echohawk, a Pawnee Nation elder and co-founder of the Denver Indian Family Resource Center, described this as one of the proudest moments of her career in Indigenous public health as she spoke to science writers at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus during the ScienceWriters2023 conference on Oct. 8.

“First Americans were first,” she said with warmth and pride in her voice during a special listening session convened at the Centers for Native American and Alaska Native Health to help inform science writers who cover Indigenous public health issues.

Echohawk and two others who spoke to science writers attribute this success to an effective public health campaign organized by Native-led organizations, which focused their vaccine messaging on themes—such as family and reverence for tribal elders—that are shared by many tribes.

Many Native Americans live in areas with few resources, so the challenges of the pandemic were compounded in their communities.

The Navajo Nation “only has 13 grocery stores across four states,” explained Crystal LoudHawk-Hedgepeth, a member of the Navajo Nation and a research associate at the American Indian College Fund in Denver. “On some tribal reservations, getting to the grocery store takes two to three hours.” At a time when toilet paper, food, disinfectants, and face masks were in short supply everywhere, the shortages were even more acute for Indigenous communities.

The Native American health services in Denver worked hard to ensure that all members of the community, in both urban and rural settings, had vaccine access.

“As an elder, I was very concerned with how to get vaccinated and all that stuff,” said Echohawk. She was concerned for her brother, who had suffered a recent family loss on top of the stress of the pandemic. “I called [the] health services and asked if they were going to be giving the COVID vaccine. And I was told, ‘We have sent someone to drive to Albuquerque…to pick up vaccines and bring them to Denver.’ And that’s been the culture.” She later accompanied her brother to a clinic to receive their vaccinations. “We felt we were in excellent hands.”

The success of vaccination among Indigenous populations was dependent on established trust among researchers and medical professionals within their local communities. Adriana Zuniga, or “Dr. Z”, is the director of dentistry at the Denver Indian Health & Family Services (DIHFS) and has worked alongside Indigenous communities for many years. During the session she described her role in the community as far from simply providing dental care: She makes an effort to ensure all of her patients feel safe, valued, and heard.

During one appointment, Zuniga said, she burned sage, with the patient’s permission. The patient immediately relaxed, saying, “I’m home.”

Zuniga enjoys adding these kind acts to her practice—which must be tailored to the traditions and cultures of individual tribes—to help put her patients at ease and build trust. “I see so much joy in my patients when they are connecting with their history,” she said.

Many Indigenous people do not have routine access to health care and can wait months to years for an appointment. In addition to enduring long wait times, Native Americans typically travel great distances to receive quality health care. Zuniga has seen patients from as far away as North Dakota in her Colorado clinic.

Zuniga considers her position to be at the forefront of integrated health care, where she not only talks to her patients about their dental needs but assesses other health concerns as well. The trust she has built up with her patients allows her to guide them toward dependable physicians and ensure their overall health needs can be met. “Patients that have moved away often still come back to ask my opinion on x-rays, test results, et cetera,” Zuniga told the science writers in attendance.

Efforts by American Indian organizations in Colorado are making positive impacts on their Indigenous communities, the panelists said. “Our clinic [DIHFS] is really offering the best health care,” Zuniga said. “Our Indigenous patients are coming into this clinic and saying ’Wow, this is what other people always get.”

Echohawk described plans for the development of the first affordable housing and health clinic dedicated to American Indian and Alaska Native communities. Denver’s 901 Navajo Street will become a multi-level building staffed with physicians and medical professionals designated to serve Indigenous communities. Additional space for housing will allow those in need to access quality medical care just a few floors away, ideally eliminating transportation barriers that affect many Indigenous patients.