Microbial answers blowin’ in the wind

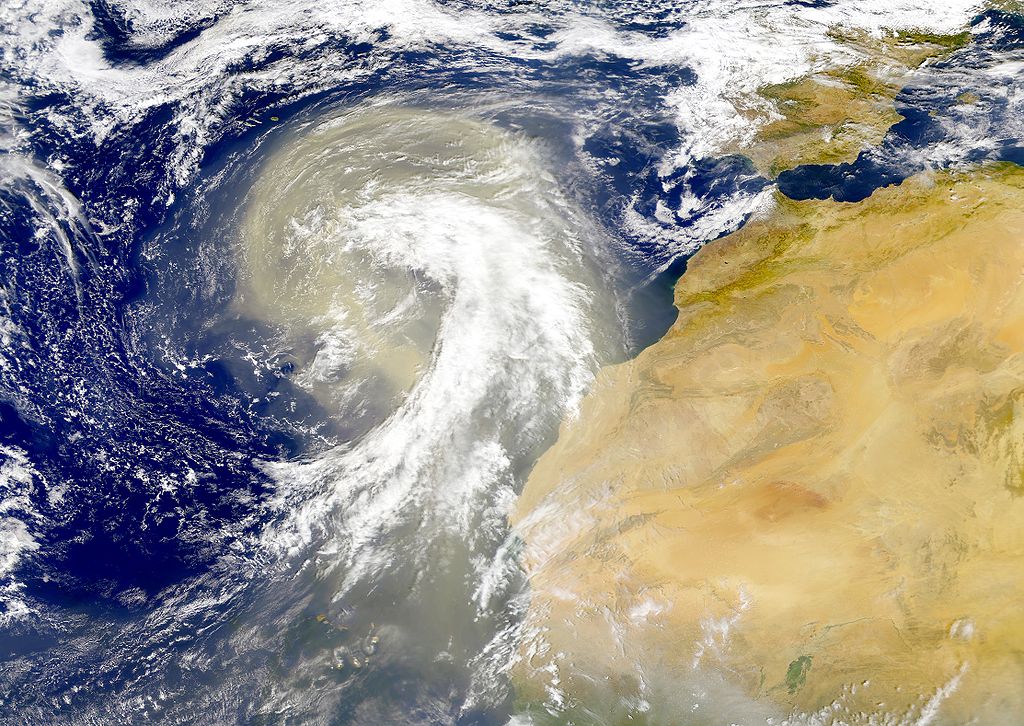

Dust plume off the Sahara desert over the northeast Atlantic Ocean seen in a 1998 SeaWiFS image. (Public domain image from NASA Visible Earth)

Globe-trotting dust storms on Earth not only carry microbes from continent to continent, they even provide clues to the ability of life to survive on Mars, says an astrobiologist who is an authority on both planets.

The interplanetary link is that dust particle–size salt crystals and their tiny passengers can be swept by wind from the ground up into regions of the atmosphere where air pressures and temperatures mimic those at Mars’s surface—conditions where lab tests already show that some of Earth’s microbes can survive.

“We’re studying something that, up to this point, has been very little studied,” said University of Florida astrobiologist Andrew Schuerger Nov. 4 during CASW’s New Horizons in Science, part of the ScienceWriters2013 meeting in Gainesville, Fla.

Huge earthly dust storms

Huge atmospheric plumes blanket the Eastern United States in more than 50 million metric tons of sub-Saharan dust annually, but little is known about just what’s blowing in the wind.

<

The answer, my friend, is what Schuerger has made it his life’s work to find out.

He’s got powerful dust collection tools in his arsenal: a supersonic F-104 Starfighter jet, high-altitude balloons, bright yellow propeller planes and tiny unmanned aerial drones.

In two weeks he plans a test flight with an orange Dust Altitude Recovery Technology, or DART, detector strapped to the underside of a plane.

“It looks a little like a torpedo, but we don’t call it that—it’s really bad to say,” Schuerger joked.

The 370-pound DART will suck dust with scoops on its nose cone under control of a scientist in the two-person cockpit.

This is the most promising way for dust clouds along the equator and elsewhere to be sampled precisely to reflect the different kinds of landscape the winds have scoured.

“The idea here is to have the capability of sampling the air in a controlled science experiment aligned precisely with the best transect, or directed path—that’s gonna give you the most science,” Schuerger said.

Harvesting dust

The drones, balloons and propeller planes will be used to harvest dust at mid- to low-range altitudes. The jets will be used for collecting more than 55 kilometers higher than Mount Everest, where conditions are so harsh it is hard to believe anything, even a germ, could come back down alive.

Here on Earth such studies are important for insight into how disease-causing microbes get blown around the planet. In the bargain, they provide a way to explore what life forms might be possible on other planets.

“If an organism can grow, survive and evolve in the stratosphere, there’s a good chance it can do the same on the surface of Mars,” Schuerger said.

For a study published recently in the journal Astrobiology, Schuerger’s team exposed 26 strains of human-associated bacteria commonly found on spacecraft to progressively lower pressure and temperature and increased carbon dioxide levels.

Bacterial survival

Many strains were tested, but as conditions approach those of Mars fewer and fewer could take it.

Just one strain of bacteria—Serratia liquefaciens, a microbe that can cause pneumonia and other illnesses—survived to the bitter end of the lab tests.

Even though the bacterial colonies seemed to die in the dish in which they had been growing, when they were restored to normal-range atmospheric conditions they began to grow again. Schuerger said such pathogens and their dust vehicles will help give us a better understanding of life at home and among the stars.

“Scientists always like to try to be on the frontier of things,” he said. “It’s very exciting work.”