Researchers strive to ease gold mining’s toll on the Amazon

An aerial view of an area in the Amazon affected by small-scale gold mining. Not only does artisanal mining result in mercury pollution—it also releases carbon that had been locked in soils and leaves behind a watery landscape in place of forest. (Photo: CINCIA.wfu.edu)

From a technical standpoint, extracting gold from soil without using mercury is very possible, says Miles Silman, the Sabin Professor of Conservation Biology at Wake Forest University.

“It’s pretty easy to do,” he explained as he answered a listener’s question following his talk at the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing’s New Horizons in Science briefings at ScienceWriters2024 in Raleigh, N.C., on Nov. 10. “You can have a table that vibrates and all the gold immediately goes to one side—and it actually is much more efficient than mercury.”

But in the western Amazon, where gold mining is causing widespread mercury poisoning, Silman said buyers at gold shops are used to seeing “foamy rock” extracted with mercury and don’t recognize the flakes that result from a vibrating table as gold. “So the [sellers] go outside, they . . . take the clean gold, they then volatilize mercury on it, they walk back in, and sell it.”

The answer, like Silman’s talk as a whole, illustrated the stubbornness and human and environmental costs of artisanal, or small-scale, gold mining, which is mostly unregulated—and also the key role of education in solving the problems associated with it.

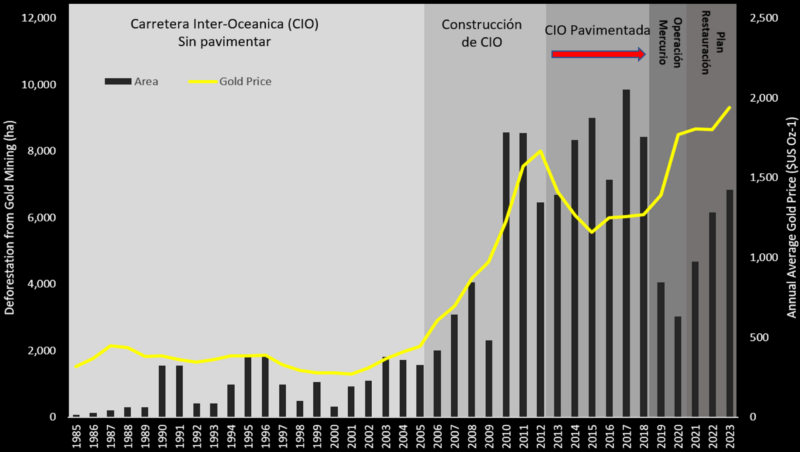

Early in his briefing, Silman explained that fans formed from sediments originating in the Andes cover large swaths of the Amazon region. “Most of those sediments—the large majority—have gold, and that gold is dispersed over vast areas,” he said. And gold mining turns out to be a major contributor to deforestation in the western Amazon.

After cutting the forest in an area down, a mining operation will use a water cannon to liquefy the earth, then put the liquid through a sluice to separate out the sediment. That sediment is mixed with mercury, which is then vaporized off to leave behind gold. Miners dump the remaining sediment in waterways, Silman said.

Despite the destructiveness of the process, “it’s very difficult to talk about illegality in this system, because in many cases there were never the conditions put in place by the governments to make them legal, so parts of the operation are illegal,” he said.

This type of mining is the biggest source of mercury entering the environment worldwide. As a result of this pollution, 7 out of 10 people in the area of the western Amazon that Silman studies have mercury levels in their bodies that exceed the World Health Organization’s recommended limits, he said. In one such community, 98% of the individuals sampled had mercury levels above the thresholds. “These were people who were living traditional lifestyles 400 kilometers away from the mining,” Silman said.

Some of this mercury comes via fish that people eat, Silman said. But it can also move from the air to tree leaves and eventually to forest soil, where it makes its way into the food chain.

In addition to testing mercury levels, Silman’s group uses drones and other types of remote sensing to get a handle on the impacts of artisanal mining. Their work doesn’t stop at defining the problem: Silman is the president and principal investigator at Wake Forest’s Centro de Innovación Científica Amazónica (CINCIA), which partners with governments and organizations in the Peruvian Amazon to carry out restoration projects and promote sustainable mining and farming practices.

Silman emphasized that the problem of artisanal mining isn’t confined to the western Amazon but is “happening in every tropical country on Earth” and is a major cause of environmental and social degradation in those countries.

However, “we have the tools that we need to see this and address it,” he said, including the CINCIA model.