Science journalism’s role in a polarized post-election America

Sunshine Hillygus, a co-director of the Polarization Lab at Duke University, discusses the results of the 2024 election at ScienceWriters2024. (Photo: Aileen Norton)

Just days after the 2024 presidential election, Sunshine Hillygus, a political scientist at Duke University, addressed hundreds of science writers gathered for the Council for the Advancement of Science Writing’s New Horizons in Science briefings at the ScienceWriters2024 conference in Raleigh, N.C. In her Nov. 9 talk, she broke down the election results and answered questions about the role of science journalists under the new administration, as they face the challenge of combating misinformation and distrust in science in a polarized country.

Hillygus, co-director of Duke’s Polarization Lab, showed data indicating that the economy was the most significant factor driving the election outcome. Well-informed science writers may find this hard to believe because media outlets have been reporting on inflation coming down and the stock market improving, Hillygus said. But absolute prices remain high, and that influences independent voters.

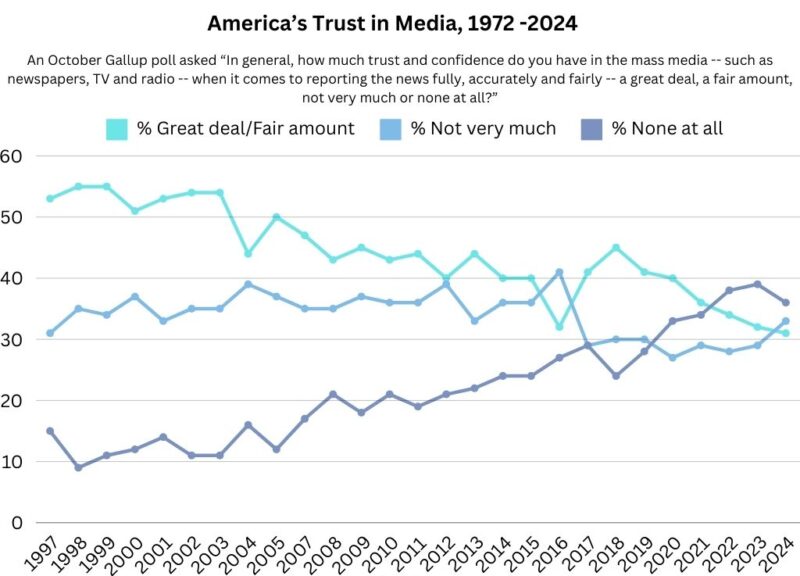

Many independents who voted Republican are not deeply engaged with political issues, Hillygus said. These voters are less likely to get their news from media outlets that offer deeper analyses and fact-checking, and instead turn to social media or podcasts. This information gap is widening: Social media is the primary news source for younger adults. According to the Pew Research Center, 54 percent of adults report getting at least some news from social media.

“There are just fundamentally different information sources for people who are not politically interested,” Hillygus explained. This trend in news consumption makes it difficult for journalists who aim to present balanced perspectives, as audiences increasingly rely on platforms that prioritize sensational content over nuanced reporting. Legacy media outlets also cater to subscribers, which could alienate a segment of the population that already feels disconnected from large institutions, she added.

In a question-and-answer session following the talk, attendees asked how science journalists can effectively address polarization without losing audiences. Jason Stoughton, a science communicator at the National Science Foundation, asked Hillygus to recommend “evidence-based practices that science communicators should adapt in our work that would help build greater trust in science.”

The answers to that question might lie in Hillygus’ research at the Polarization Lab. Members of the lab study how technology and social media fuel political tribalism. In one study, for example, researchers assigned Democrats and Republicans to follow a Twitter bot posting content from the opposite political party. Republicans exposed to liberal content became more conservative, while Democrats exposed to conservative content later leaned slightly more liberal. This finding suggests that exposure to certain types of opposing information can reinforce existing beliefs, Hillygus said.

In an interview after the briefing, Hillygus suggested that catastrophic language around topics like climate change might turn some conservative readers away. “For people who are not reading the headlines about climate change, the minute you say ‘climate change,’ they move on,” she explained.

Journalists might consider framing these issues in a way that resonates with people’s personal experiences. For example, communities recently impacted by extreme weather events, such as western North Carolina after Hurricane Helene, may be more receptive to discussions on resilience and preparedness. By focusing on how these events impact everyday lives, journalists can present climate-related issues in a way that encourages engagement across political lines.

A phenomenon called “expectation violation” can also have an impact. When someone who traditionally opposes a certain view publicly supports it, this unexpected stance can be more persuasive than a predicted endorsement, Hillygus explained in her interview. “Assumption about bias is huge—the assumption is that academics are biased, that journalists are biased.”

That means that for some audiences, journalists aren’t trusted messengers on topics like climate change, Hillygus said. But when a conservative leader voices support for environmental policies, this violation of expectations may encourage audiences to reconsider their stance. Science journalists could reach more audiences by featuring voices that cross traditional political boundaries, creating a sense of trust and openness among skeptical readers.

The event ended with a call to action for journalists. In response to a question about connecting with low-information voters, Hillygus replied, “I want to pitch that question back out to you guys, about how to infiltrate the information streams.”