CASW-affiliated contributors, editors share tips in Tactical Guide

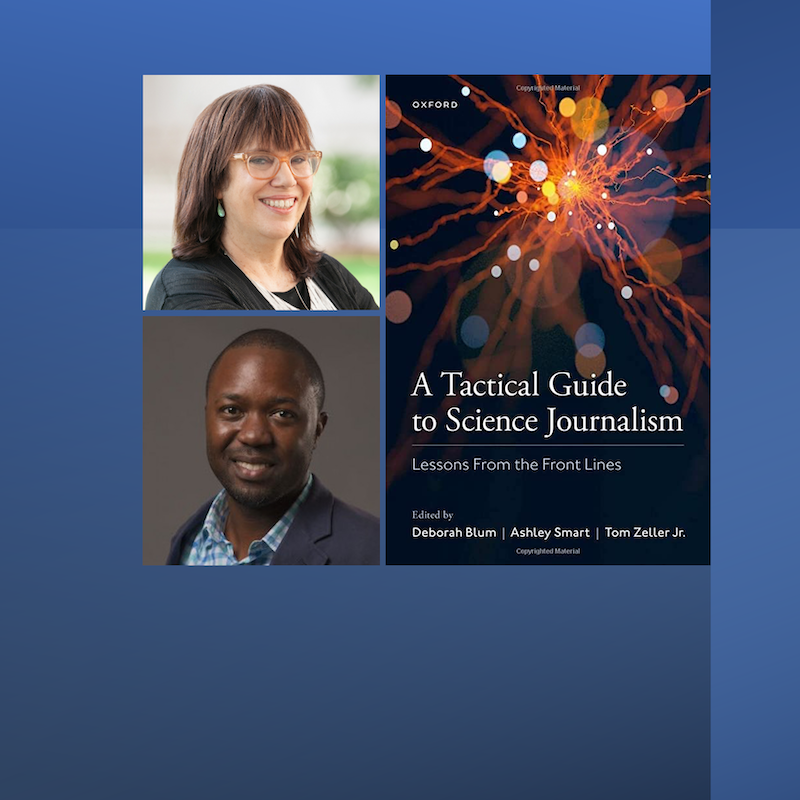

Deborah Blum and Ashley Smart, editors of A Tactical Guide to Science Journalism. Book cover courtesy Oxford University Press

A valuable new guide is available for the science journalist’s bookshelf. A Tactical Guide to Science Journalism: Lessons from the Front Lines brings together in one place insights from award-winning science journalists about the foundations of the profession, the craft of storytelling and investigative reporting, perspectives on a wide range of science beats and much more.

The editors, two of whom are CASW board members, conceived of the book as a tool for journalists who want to help their audiences understand the increasingly complex science in our lives. Among the contributors are four additional CASW board members and six winners of CASW awards and fellowships.

“We’re at a moment where science journalism—meticulously researched independent inquiry into the workings of science and its profound effects on society—matters more than ever,” Tactical Guide editor Deborah Blum, director of the Knight Science Journalism program at MIT and a longtime board member, told CASW. “The Covid-19 pandemic amplified this point, the anti-vaccine and misinformation movements amplified it again, and the growing dangers to the planet posed by climate change underlined it.”

Fellow editor and board member Ashley Smart told CASW his biggest hope “is that the book will give aspiring science journalists —as well as experienced science journalists—tools and inspiration to go out and tell stories that make an impact.” Smart is associate director of the KSJ program and senior editor of Undark magazine, where Blum is publisher.

The editors add that peeking behind the curtain to see how stories are made is valuable for non-journalists as well. In the book’s introduction, they write: “The lessons offered are equally valuable to journalists across the board who want to gain the ability to add smart science coverage to their beats as well as for scientists curious about the ways of journalism, readers wondering about how stories are told, and more.”

Together, Blum, Smart and Tom Zeller, Undark‘s editor-in-chief, recruited top science journalists to write about an aspect of reporting, writing, editing, and fact-checking science stories, opinion pieces, videos, and books around the world. Other chapters cover building trust, marketing one’s work, and the challenges of specific science beats.

Here are some of the insights they shared with CASW or offered in the book, published in June by Oxford University Press.

Working with Sources

Azeen Ghorayshi, New York Times science reporter (Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award 2014)

“Knowing how to navigate source relationships is crucial when doing any type of reporting,” writes Ghorayshi in a chapter about finding and vetting sources. She touches on mapping out people to talk to, asking the right questions, using social media, convincing sources to engage with reporters, and when to use anonymous sources. “In the end,” she writes, “building trust requires showing that you are sensitive and thoughtful with sources—and publish stories that they view as diligent and fair. This can help you gain a broader network of people who come to you with future tips, as well as get you sources that you can turn to for information time and time again.”

Maggie Koerth, FiveThirtyEight.com senior science writer (CASW board member)

“Statistics don’t have to be scary,” Koerth told CASW. “There’s a lot of intuitive stuff you can do that will make your reporting smarter and it doesn’t require you to suddenly become super good at math if that’s not a thing that feels natural to you.”

In her chapter on working with statistics, she notes that data are not objective facts and should be approached with caution. “The best tips and tricks for working with data,” she writes, “are things that help you interrogate numbers the same way you’d question a living, breathing source.”

Telling Science Stories

Alicia Chang, Associated Press health, science and environment editor (Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award 2009)

Alicia Chang echoes Koerth’s advice to ask lots of questions. In her chapter on news reporting she writes, “We must be up front with what we know and, more importantly, what we don’t know and still need to learn. You need not be an expert in everything, but you should question everything. Even with the clock ticking, stories should carry different voices and be representative of society.”

On beating deadlines, she offers this nugget: “Invest in spadework off deadline. Identify several core subjects you’ll likely cover again and again. And then make cheat sheets.”

Blum told CASW that she hopes her chapter on story structure will “provide writers with this set of tools essential to building a good story and to encourage writers to think about which structures best suit the work they are doing.”

In the book she writes that, “good narrative writing is often as much technique as it is talent, sometimes more.” She adds that a story needs structure, what she calls “journalistic architecture,” to pull the reader through from start to finish. Different types of stories require different shapes: inverted pyramid, diamond, narrative arc, zipper and braided narratives, or broken-line and layered narratives. Story structures, she writes, can serve as a “reminder that plotting a story in advance is one of the smartest things we do.”

Charles Seife, professor, Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute at NYU (Nate Haseltine Graduate Fellow 1995)

In his chapter on data storytelling, Seife offers assurance that good data journalism does not require programming skill. It’s all about asking the right questions in the right ways.

“Just like human sources, data sources are most useful when you’ve got an angle in mind––questions you’d like your data set to answer or a gap in your knowledge that you’d like it to fill,” he writes. “Interrogate it with a sense of purpose, and it’ll drive you more directly to a story than if you noodle around and hope for an idea to emerge.”

Covering Disease, Physics, Earth Science, Policy

Helen Branswell, STAT senior writer on infectious diseases and global health (Victor Cohn Prize 2021)

Infectious disease is an inexhaustible beat that often entails reporting on breaking news, writes Helen Branswell. Her chapter on the topic covers ways to approach this kind of science reporting including how to get up to speed and find experts.

“One of the critical things about infectious diseases reporting—any science reporting, really—is to talk to the right people,” she told CASW. “Go to people who specialize in what you’re writing about, not a generic ‘expert’ who doesn’t know the issues you’re exploring in depth. Trust people who decline to be interviewed because they don’t know enough about the topic; find out what is in their wheelhouse and use them when you’re writing about that. And be very wary of silver bullets. In most outbreaks I’ve covered, there’s been a hydroxychloroquine or an ivermectin. Most silver bullets turn out to be tin.”

About his chapter on covering physics, Smart told CASW, “the biggest joy of writing my chapter on physics was that I got to speak with some of my favorite writers — incredibly talented people like Anil Ananthaswamy, Charles Day, and Natalie Wolchover — about how they approach their craft.”

In the book he describes the challenge of covering physics this way: “Like physicists, we physics reporters strive to capture the wonder and weirdness of a pursuit that continually pushes the limits of human understanding.” One technique to help make the abstract concepts of physics relatable to readers is to focus on physical details.

But he urges writers to be careful. “In the struggle to make physics seem relatable, it’s easy for a reporter to overdo it,” he writes. “But never underestimate the capacity of average Jane and average Joe to be curious for curiosity’s sake—to appreciate the wonder of a world that is mysterious beyond anyone’s wildest imagination and to marvel at the quintessentially human quest to decipher it. If you can convey that sense of wonder, if you can satisfy even an ounce of that curiosity—and if you can do so with reporting that is accurate and authentic—that may well be all the relatability you need.”

He told CASW that even though the subject is difficult, “you can’t cut corners. You really have to put in the work of understanding the material if you want to write about it clearly. That’s true for most science writing, but it’s paramount in physics.”

Betsy Mason, freelance science journalist (CASW board member)

Mason described her chapter as a pitch for covering earth sciences. “It’s an uncrowded beat filled with underreported stories and the chance to get into the field with scientists,” she told CASW.

“Stretching from Earth’s core to the crust of Mars and beyond, the expansive nature of the earth sciences yields countless types of stories and plenty of undercovered areas,” she writes. “Much of this territory has the benefit of being, well, down to earth.”

Her final word is a call for balance: “Reporting on natural hazards is also a great opportunity to do meaningful service journalism that might even save lives, so it’s important to provide the proper context for readers and avoid sensationalizing these stories.”

Dan Vergano, Grid News science reporter (CASW board member)

“Reporters routinely ignore most science policy news because they tend to see it as the grinding of governmental or industrial activity or boring announcements of blue-ribbon panels and investments into promising research,” Vergano writes in a chapter on covering science policy.

Digging deeper often reveals more is at stake. “The biggest science stories of this century (at least so far)—the Covid-19 pandemic and climate change—are riddled with science policy failures, to use the term of art in policy analysis (yes, this exists) for screwups that hurt people.” Both stories, he writes, “underline the need for science reporters to go beyond reporting discoveries to investigating decisions about science.”

“Just like ‘follow the money’ is the key to investigative reporting, ‘follow the science’ is the key to science policy reporting,” Vergano told CASW. “In other words, does the science in truth justify the choice(s) embodied by the policy, or not?”

Media Models, Trust, Reporting Risks

Thomas Lin, Quanta Magazine editor-in-chief (CASW board member)

Thomas Lin shares his optimism about the field in a chapter about new models for science media. “Despite the decline of science news in newspapers and the recent struggles of some legacy science magazines, by at least one measure there has never been a better time to be a science journalist,” he writes. “Mirroring the transformation and fragmentation of the media landscape more broadly, there are now more flavors of science journalism than ever before. This means more options and more entry points for writers breaking into the profession.”

“Whatever kind of science you want to write about, there’s probably a publication that caters to an audience that wants to read about it,” Lin told CASW. “A smaller digital science outlet might be a steppingstone to a big brand name publication, or it could turn out to be the destination you were looking for all along.”

Apoorva Mandavilli, New York Times health and science reporter (Victor Cohn Prize 2019)

“Misinformation about science is as old as science itself,” writes Apoorva Mandavilli in a chapter about building trust and navigating mistrust. “As a society, we have not done a good job of helping people understand that science is slow and iterative, rather than a series of dramatic results. That puts the onus on journalists to describe not only individual findings, but also where they fit into what was previously known––and what is still unknown.” Context is key. When it’s missing, she writes, articles can overhype and mislead.

“Trust begets trust,” Mandavilli told CASW. “Be skeptical of every source, but if you want to build trust with readers and help them navigate misinformation, trust them and their ability to understand complexity. Be honest with them and don’t withhold facts—not ‘for their own good,’ not because they may not understand it, and not because they may misuse it. There is no excuse for not telling the whole truth.”

Richard Stone, HHMI Tangled Bank Studios senior science editor (Nate Haseltine Graduate Fellow 1990)

“Dozens of authoritarian regimes and police states exist today,” Richard Stone writes in a chapter on reporting in this context, “but for a science journalist some are especially intriguing because of their reliance on science as a pillar of society or means of staying in power.”

“For intrepid journalists, reporting from inside authoritarian regimes presents unique risks and rewards,” Stone told CASW. Some of the risks of reporting in authoritarian regimes Stone describes include incarceration, constant monitoring by authorities, constraints on whom you may interview, endangering sources, or worse. Stone told CASW that he shared his thoughts on “how to prepare for and carry out a reporting trip to forbidding countries like Iran, North Korea and Russia such that you not only come back safely with a great story, but also protect the sources and fixers you work with.”