Science, activism and domestic violence: A Nicaraguan story

Mary Ellsberg speaking at ScienceWriters2018. (Photo by Mark Scavone.)

When Mary Ellsberg and other women’s activists in Nicaragua drafted a law prohibiting domestic violence, the politicians “pretty much laughed in our faces,” she told attendees at the ScienceWriters2018 conference Oct. 14. “They said that it wasn’t really that big of a deal, domestic violence. If we really wanted this law to pass, we needed to come up with hard numbers to show that domestic violence was really a problem in Nicaragua.”

After that experience, Ellsberg, professor of public health at George Washington University, began her career in epidemiology, using science to both estimate the prevalence of violence against women and implement ways to prevent that violence.

Giving the opening presentation of CASW’s New Horizons in Science program at ScienceWriters2018, held on the GW campus in Washington, D.C., Ellsberg told the story of how epidemiology can prevent violence against women and girls. She offered her work in Nicaragua as a case study of the power of science and activism.

After conducting the first domestic violence prevalence study in Central America in 1995, Ellsberg and her colleagues had the hard numbers. They interviewed 488 Nicaraguan women in the city of León and found that one in two had experienced physical or sexual abuse by their partner at some point in their lives.

The research group published their findings in the journal Social Science & Medicine, but they wanted to be sure that the affected women had access to the information, too. “We see the goal of our research not so much in the peer-reviewed reports,” said Ellsberg. “Those are important, but we care more about making sure people on the ground have the information they need to move forward in their activities to end violence.”

Ellsberg and her team disseminated their findings across Nicaragua in documents and articles in Spanish. The group combined their science with advocacy and took out a full-page newspaper advertisement calling for signatures to petition for a law against domestic violence. After 16,000 women sent in letters supporting the petition, Nicaragua passed the law. “This was my first experience with how powerful science can be when in the hands of the right people,” said Ellsberg.

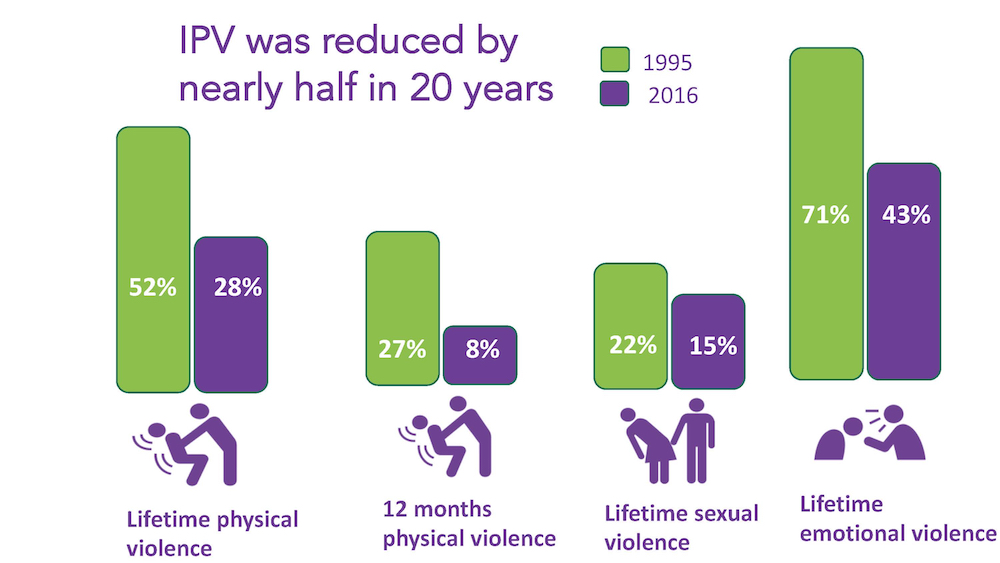

And according to a follow-up study in Nicaragua 21 years later, the impact of that science was powerful. Ellsberg explained that likely as a result of the law’s passage as well as cultural changes, like more women seeking help and reporting incidents to police, Nicaraguan women reported lower rates of intimate partner violence. Rates of physical violence decreased by almost half.

But Ellsberg reminded the science writers that rates of violence are still high. According to Ellsberg, the 2016-17 follow-up study found that Nicaragua had done away with services for survivors, like women’s police stations, and a conservative government espouses the view that domestic violence is a family matter. Her science has shown that violence is preventable, but prevention requires sustained efforts by the government and society.